FOR THE LATINX RESEARCH CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY

Puro Corazón:

The Heartwork of Melanie Cervantes

By Moi Santos

The latter half of the 20th century in the United States was characterized by a series of successful social and political movements that sought to contest the conditions of marginalized peoples in the U.S. and abroad. In addition to the emergence of a growing political consciousness, this period saw the proliferation of the poster as a politically engaged tool. As Cary Cordova notes, “the affordability of the technology, both in terms of production and distribution, along with a poster’s capacity to synthesize a movement’s objectives, spurred production globally” [1]. To this day, the poster remains an essential tool for raising awareness, fostering unity, and inciting action.

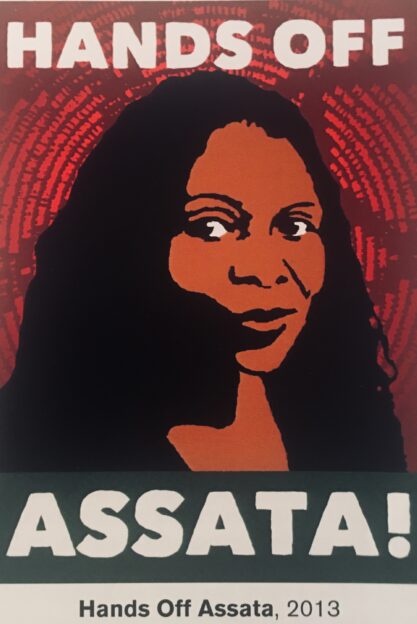

I first encountered Melanie Cervantes’ work on Facebook in 2014. I came across an image of Assata Shakur with the text: “HANDS OFF ASSATA!” At the time, President Obama had just announced the restoration of diplomatic ties with Cuba, which incited questions regarding Shakur’s extradition, who was granted political asylum by the Cuban government in 1984. Unlike the articles and images circulated on the news, this image moved me; it made me feel personally responsible for ensuring Assata remained safe. I felt empowered. I wasn’t the only one. I soon encountered dozens of Cervantes’ pieces in social justice spaces, the streets, and book covers. Distinguished by the use of vibrant colors and social justice messages, this is just one of the effects of Cervantes’ work.

Born in Harbor City and raised in the South Bay of Los Ángeles, the Xicanx artist first moved to the Bay Area in 2002 in pursuit of a B.A. in Ethnic Studies from UC Berkeley, where she was able to work alongside Norma Alarcón and Celia Herrera Rodríguez. In 2007, a year after learning how to screenprint, Cervantes and Jesús Barraza, co-founded Dignidad Rebelde, a graphic arts collaboration that produces screen prints, political posters and multimedia projects grounded in Third World and indigenous movements. Advancing the legacies of cultural producers like Emory Douglas, Yolanda M. Lopez, Rupert García, and Juan Fuentes, Cervantes has emerged as one of the most prominent and important contemporary visual artists. In her first solo exhibit, Puro Corazón, Cervantes beautifully highlights the inextricable connection that exists between art, spirituality, activism, and the body. Curated by Cervantes, the selected works of Puro Corazón function as remedios that confront and contest the legacies of colonialism, genocide and exploitation. Spiritual activism and curanderismo is at the heart of Melanie Cervantes’ extensive oeuvre.

Chicana feminist, Gloria Anzaldúa defined spiritual activism as “spirituality for social change, spirituality that recognizes the many differences among us, yet insists on our commonalities and uses the commonalities as catalysts for transformation” [2]. Guided by the principles of Xicanisma and Zapatismo, Cervantes harnesses art to build people’s power, amplify people’s stories, and put the art back into the hands of the communities who inspire it. As Dylan Miner notes, the work of Dignidad Rebelde, “challenges notions of heterosexist and patriarchal Xicano visualities…contest[s] settler-colonial normativity within the field of Chicano art history, while also queering settler-colonial notions of the nation-state” [3]. Thus, Cervantes operates from a decolonial pedagogical praxis and this is felt through the title and layout of the exhibit. Puro corazón roughly translates to pure heart, pertaining to purity of the heart, but also connoting an amount of heart being put into something, like this exhibit. As the title and previous work suggest, heart and love are essential to the work of Cervantes. Putting corazón into something is an act of resistance. It is an exchange of energy and as bell hooks has pointed out, a verb [4]. It is an act of resistance because it challenges the capitalist notions of labor, productivity, value, and knowledge. A capitalist praxis values quantifiable data and deems non-western modes of knowledge production and distribution as less valid. Furthermore, this is racialized as it is used to discredit the underground and creative economies created by marginalized communities.

Writing about queer latinidad, Juana María Rodríguez, discusses how as Latin@s and queers, what has come to define us is our dramatic gestures [5]. Yet, she points out that our racialized excess is already outside the norm of what is useful or productive and thus must be contained. Thus it is this excess, this expression and carnality of gestures, sexualities, desires, and knowledges that are a threat to the accepted modes of knowledge. Cervantes rejects the idea that passion or emotion isn’t rational or that it needs to be contained. We can see this in the bold vibrant colors that aestheticize her work and her body. The first time I saw Melanie, I was coming out of BART on 12th Street. It was a warm summer afternoon almost evening and as I am making my way to my bus stop, I catch a glimpse of some bright pink lipstick, a yellow sweater and black and white checkered pants. Furthermore, this rejects the western binary between body and mind. Embedded within the word corazón is the word razón, which is spanish for reason. Thus, as an analytic deployed by Cervantes, co-razón is a re-membering of reason and passion, of the body and the mind.

This is what Anzaldúa has called the Coyolxauhqui imperative, that is, the process of moving from fragmentation to wholeness. Anzaldúa notes that this is a result of colonialism and that the process is complex and not necessarily linear or smooth, but that this is the path of the artist. Regarding the artist as a shamana, for Anzaldúa, the artist uses imagination to impose order on chaos, provide language to distressed people, and ultimately, arrive at a collective understanding of the human experience through creative expression. Thus, Cervantes’ artworks can be understood as remedios to the dis-membered subject, and by extension Cervantes herself a curandera transforming the world by “imagining it differently, dreaming it passionately, and willing it into creation” [6]. In attempting to move us from that place of fragmentation to wholeness, Cervantes employs not just the sense of sight, but the sense of sound and the physical act of movement as well. Rather than display all the works at once in the main room, Cervantes moves away from wanting people to simply see the art and instead opts for the audience to experience the art. She successfully does this by creating an exhibit that spread into various rooms and parts of the house as well as creating a playlist to guide and ground the audience through the exhibit. This underscores Cervantes’ intentionality and understanding of the power of art to heal and transform.

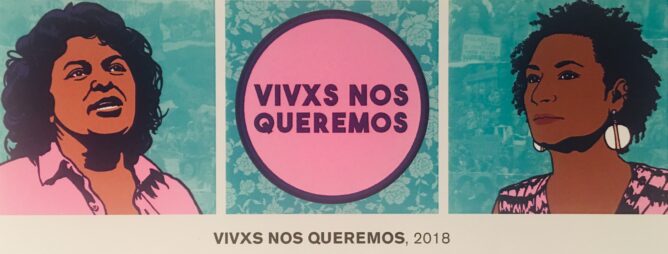

Along the stairwell we are greeted by images of various activists including Joaquín Murrieta, Magdalena Mora, Gloria Anzaldúa, Berta Cáceres, and indigenous activist Rigoberta Menchú, and political activist Marielle Franco. In the image of Rigoberta Menchú, only the top half of her body is visible. She is positioned off center to the right facing the audience. She wears a textured magenta huipil with a matching head wrap and neck piece. Behind her are a mountain and the visible blue sky. In the image of Marielle Franco, Franco looks out into distance. Her head and hair take up the majority of the frame. The background is composed of a collage of images of Marielle’s community activism. In both of these images, the background is just as important as the subject in the foreground. Through the use of layer and texture, Cervantes creates symbolically layered political images. For instance, in the portrait of Menchú, the sky and the mountain stand firmly behind her, almost as if she is protecting them. In 1992, Menchú was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her activism which has prompted awareness of the genocidal acts against indigenous people. At the same time, the mountain and the sky are also positioned as if in support of her. The mountain protects her back and the sky guides her path. This demonstrates a decolonial understanding of the relationship between humxn and land; that is, one that is symbiotic and based on mutual respect.

Similarly in the portrait of Franco, the background is made up of the various causes Franco believed in. Franco was a councilwoman from Rio deJaneiro who was assassinated in March. She was a queer black Brazilian woman from one of the poorest favelas in Rio de Janeiro. Her voice in government and in the streets was important to a lot of people who, traditionally and contemporaneously are still silenced and ignored by the State. Cervantes beautifully captured this by constructing a collage of the various communities she belonged to. By creating this background, Cervantes compels her viewers to engage with the image on a more personal level, literally. In order to make out the series of images that make up the background, one must get close to the image, it forces us to linger and be face to face with her, face to face with her communities. The collage does not allow for the work and image of Marielle to be erased as we are made to interact with her and her legacy up close.

In the same way that the veins pass blood and oxygen to a beating heart, the images on the stairwell pass the vital components of our activism, or heartivism. Ending the series on the stairwell with a stunningly beautiful image of a corazón sagrado, Cervantes reminds her audience to lead with our hearts. Each of the activists featured in the stairwell series, were committed to bringing justice to certain communities. Cervantes’ decision to begin the exhibit with these images is a honoring of the leaders who have led with their heart to combat systemic forces of oppression and a reminder that our activism must be for the people and come from our heart, not our ego. Like Marielle’s, our search for justice must be intersectional. Like Menchú’s, our activism must also center indigenous peoples and protect the Earth. And essential to our activism and to dismantling these forces is our community.

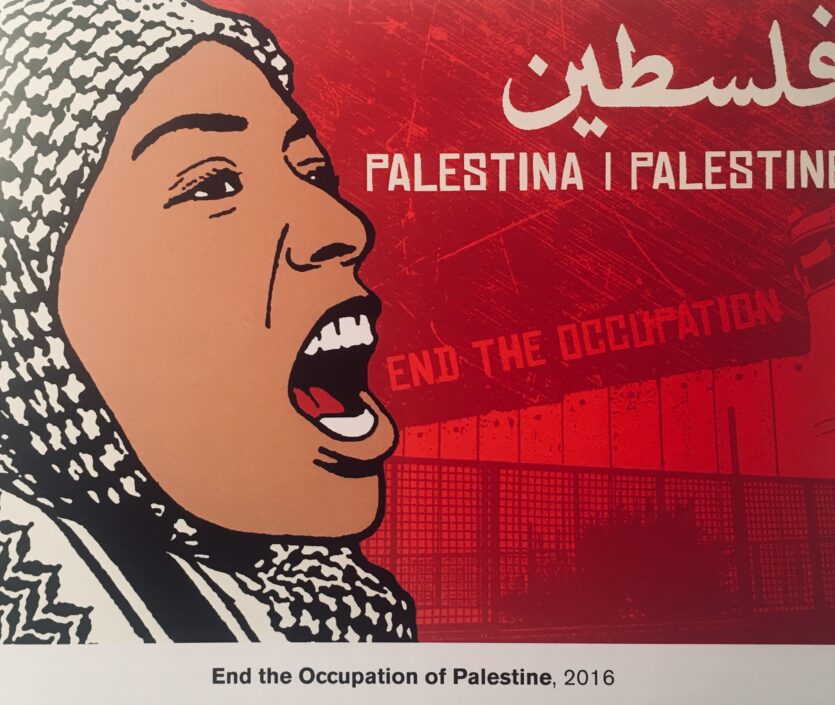

Essential to Cervantes’ practice is using art to inform and transform. Through her art, Cervantes illustrate stories of struggle, resistance, and triumph. In “End the Occupation of Palestine” (2016), we are presented with the image of a young woman wearing a keffiyeh with her mouth open as if she is shouting. In the background, among other things, we see the words “end the occupation” which appear to be coming out of her mouth. Contrasted against the red background, in white text is the word

Palestine, spelled in Arabic, Spanish, and English. This image speaks to the Israeli-sanctioned occupation of Palestine as well as the need for other marginalized communities to be in solidarity with the struggle for liberation in Palestine. This is emphasized through the compositional techniques of Cervantes whose enlarged image of the woman takes up the left third of the poster, a contrast from the very little attention mainstream media and politics pay to the Palestinian struggle. Additionally, the use of red both speaks to the violent atrocities occurring as well as the urgency felt in the region by Palestinians. In this way, one can hear the piece.

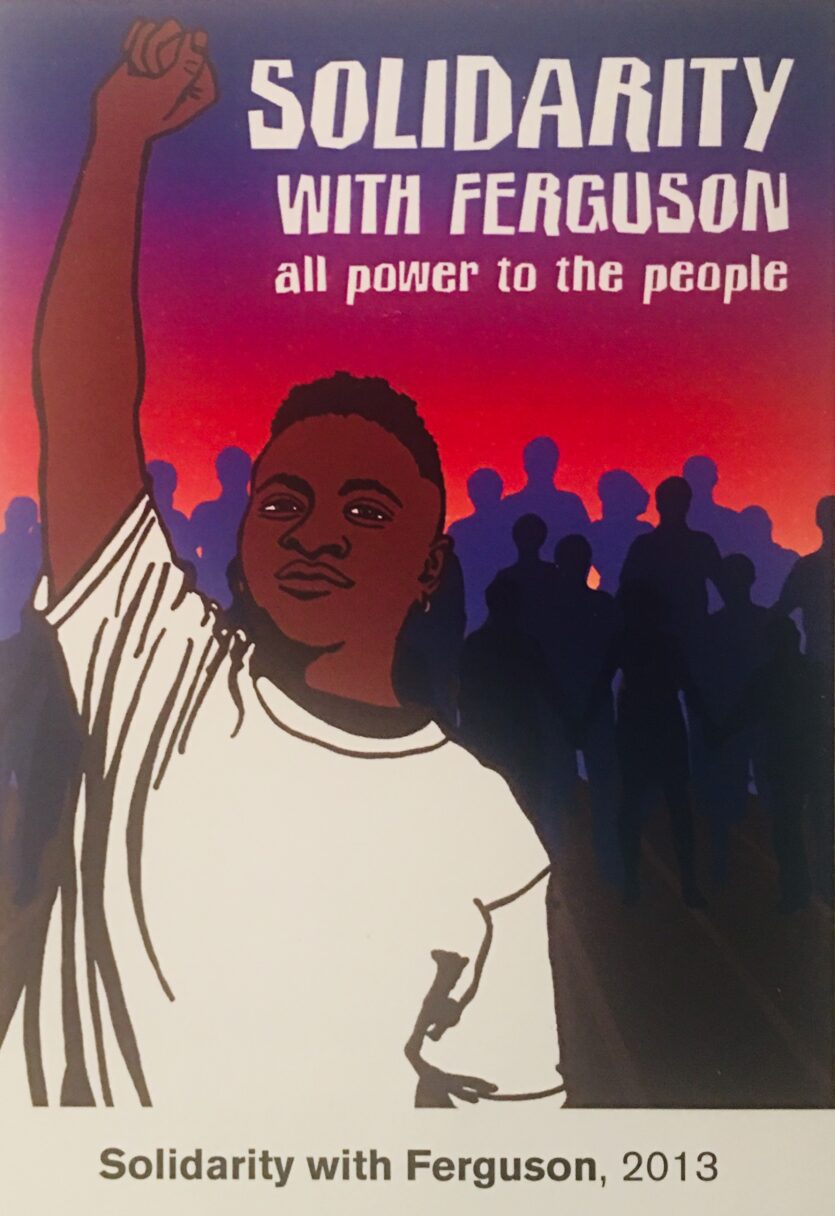

The theme of building solidarity and cross-cultural understanding is also present in Cervantes’ “Solidarity with Ferguson,” which features a young Black activist with their fist up in the foreground. The background is composed of the silhouettes of people walking hand in hand toward the audience in solidarity with the young person in the center. In these two images Cervantes underscores the importance of solidarity as well as the personal responsibility she feels as an artist to create art that produces “knowledge and conocimiento”[6]. Rather than solely focus on the struggles and triumphs of the Xicanx community, Cervantes instead opts to use her skill to combat the “divide and conquer” tactics used by the state. In the “Solidarity with Ferguson” the use of orange in the background imbues the piece with a sense of potentiality. As the sun rises, so do the people. The silhouettes emerge from the horizon. Upon closer inspection, one can see what appear to be stars. Combined, these elements

ignite a sense of hope and support. They tell the people of Ferguson that they are not alone and remind them that protesting and demanding the justice is not futile. Cervantes presents these movements as sites of possibility; the possibility for connectivity, for justice, for change.

Central to her work is underscoring the personal as political, which she executes in Room 1 of her exhibit. The images lining the walls of this room are of women activists. Utilizing written text and bold colors, Cervantes creates a vivid archive of women who have contributed to making the world a more just place, yet are often erased from history. Among the images in this room is Sylvia Rivera, who along with Marsha P. Johnson, initiated the Stonewall Uprising. Commonly regarded as the birth of the Gay Rights Movement, the Stonewall Uprising occurred after police had raided the Stonewall Inn, one of the few establishments that welcomed openly gay people, in New York. Yet this history is so often erased that the in the official trailer for the 2015 film, Stonewall, it is a cisgender gay man that is portrayed as throwing the brick that incited the riot. As Martin F. Manalansan IV notes in “In the Shadows of Stonewall: Examining Gay Transnational Politics and the Diasporic Dilemma,” the globalization of a gay identity and with Stonewall as the point of liberation for gay and lesbian people, has not benefited everyone in the same way and instead left some people in the “shadows.” Despite the increase in positive LGBT representation and legislation, queer people- and trans women of color are some of the subjects the rainbow does not extend to. The biographical film about gay rights activist and politician, Harvey Milk (2008), won two academy awards by 2015, ABC’s Modern

Family (2009-present) has become a household name, having seven successful seasons and multiple awards. Just two years after Modern Family’s premiere, Don’t Ask Don’t Tell (DADT) was repealed. The Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which prohibited married same-sex couples from collecting federal benefits, was overruled.

While these legislative and representational strides are important, the reality is that they typically meet the needs of white middle-class cisgender gay and lesbian Americans, and not the needs of queer and trans people of color. 60 percent of LGBT hate crime victims are people of color. 2017 was the deadliest year on record for transgender people, with a majority of the victims being women of color. Thus, Cervantes’ image of Rivera creates an alternative archive. Through the use of bold colors, Cervantes reclaims the colorful imagery associated with the mainstream gay movement, pointing to the ways in which the voices and efforts of and by transgender women of color have been louder, bolder and not parallel with the traditional gay and lesbian movement. At the bottom of the image, Cervantes includes a quote from Rivera: “we didn’t take no shit from nobody. we had nothing to lose.” This quote contextualizes the socio-political positionality of trans women of color and calls into question who has truly benefited from the LGBT movement, while highlighting and honoring the tenacity of the women of color who have fought, with all of their might and heart, in the face of various obstacles.

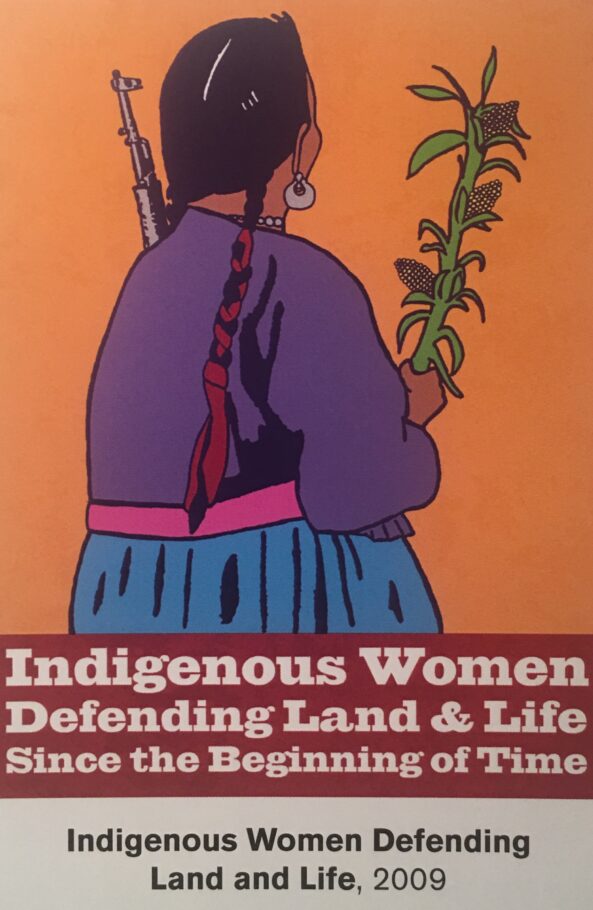

In the second room, Cervantes honors the indigenous women who have fought to defend land, life, and livelihood. In one particular image, against aluminous yellow background, an indigenous woman stands in the center, wielding a stalk of corn and a rifle. Her back is to us and in the foreground is the text, “Indigenous Women Defending Land & Life Since the Beginning of Time.” The image honors the legacy of indigenous women defending the land. The text, written in white and placed on a red background within the larger color pattern of the piece, firmly states the resilience of indigenous women throughout history. This is further emphasized with the corn stalk she is holding as a weapon; as a mode of survival, demonstrating that she will not back down or be intimidated. The use of the corn stalk is important because corn or maíz is more than a crop, but it is a symbol of quotidian life. Not only does maíz provide food security, but it also sustains indigenous people at the economic and spiritual level. Thus, corn is inextricably linked to survival and the indigenous fight for sovereignty. As an audience, her back is to us, and we are, in a way, able to see things from her perspective.

Cervantes’ art is strongly tied to her background as a Xicana and this is evidently seen in her “Viva La

Mujer” image in the third room. “Viva La Mujer” is a collaboration between Cervantes and Barraza. In the center is a portrait of a Xicana, drawn by Cervantes, mixed with a pattern Barraza created from an ancient Olmec stone stamp. The joining of the past and the present, combined with the declaration “Viva La Mujer,” affirms the belief that muxeres must be at the center and forefront of transformational social change; and Cervantes does not limit the means by which that change must be achieved.

In the fourth and final room of the exhibit, along the walls are various images of other cultural producers: Lila Downs, Selena, James Baldwin, for instance. This room was a powerful end/beginning of the exhibit as it challenges the toxic mentality that activism has to look a certain way. By portraying other artists in the exhibit, Cervantes marks the importance of pop-culture as a didactic site of resistance. Furthermore, it presents creativity as a powerful weapon with which to challenge systems of oppression. This is further emphasized with the text pieces Cervantes has included which include quotes about revolution, resilience, and our ancestors. In this way it is Cervantes’ call for her audience to nourish and harness their creativity because it is the greatest weapon at their immediate disposal.

Like artists who came before her, Cervantes uses art to transform. Taken as a whole, the selected works demonstrate Cervantes’ spiritual approach to art that sets her apart from her predecessors and contemporaries. In Puro Corazón, Cervantes takes us through the four chambers of her heart, demonstrating the creative production of following her heart’s lead. The remedio brewed from intention and cariño. Harnessing her heart as a remedio, a muscle, an organ, an instrument, a weapon, an armor, a vessel, a home, Cervantes takes on Gloria Anzaldúa’s call to action and “lights up the darkness” one beat/squeegee run at a time.

[1] Cordova, Cary. The Heart of the Mission: Latino Art and Politics in San Francisco, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017.

[2] Anzaldúa, Gloria. Light In The Dark/Luz En Lo Oscuro:Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality. Duke University Press, 2015.

[3] Miner, Dylan. Creating Aztlán: Chicano Art, Indigenous Sovereignty, and Lowriding Across Turtle Island. University of Arizona Press, 2014. 199.

[4] Hooks, Bell. All About Love: New Visions. William Morrow Paperbacks, 2018.

[5] Rodríguez, Juana María. Sexual Futures, Queer Gestures, and Other Latina Longings. NYUPress, 2014.

[6] Anzaldúa, Gloria. Light In The Dark/Luz En LoOscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality. Duke University Press, 2015.

Revista N’OJ ©<script>document.write( new Date().getFullYear() );</script> All right reserved.