FOR THE LATINX RESEARCH CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY

Zapatismo at Twenty-Five and its Impact on Chicana/o Activism: Part One

By Pablo Gonzalez

January 1, 2019 marked the 25th anniversary of the Zapatista rebellion in Chiapas, Mexico. An indigenous rebellion coined the “first revolution of the 21st century.” Since then, the Zapatista indigenous struggle has grown in numbers and inspired millions more across the world. While national and international media attention no longer focus on their initial call to arms, the Zapatistas have continued to organize throughout various regions of Chiapas, primarily around the concept of autonomy. Building schools, clinics, women’s cooperatives, and alternative forms of governance, the Zapatistas have become a beacon against neoliberal capitalism. In barrios across the United States, Zapatismo has inspired Chicanas/os to produce new forms of political solidarity, a rejuvenated cultural renaissance, and new forms of doing politics. The following essay is a personal reflection of Zapatismo at twenty-five years and its impact on Chicanas/os/x in the United States.

A People without a History

I often jump start my one hundred-twenty student “Introduction to Chicana/o History” course with a lesson titled, “A People without a History.” I begin with the October 12, 1992 protests. Protests occurred in Quito, La Paz, Mexico City, San Juan, San Francisco, Sacramento, and San Cristobal de las Casas all held a similar banners, with similar messages: resistance not discovery. Across the world, nation states commemorating October 12, 1992 as the anniversary of Cristobal Colon’s arrival to the “New World” commissioned murals, paintings, statues, and funded academic conferences to reinforce the impact and legacy of October 12, 1492. With little press, the manifestations against the commemoration of Columbus’s arrival marked a distinctly different moment. The protesters were doing so under the banner of “500 years of resistance,” a challenge to the dominant narratives of the modern/colonial world.

In San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico, thousands of Mayans marched on the town October 12, 1992, shocking the caxlanes or San Cristobal mestizo population. The anti-indigenous racism embedded in everyday life had erased the Tzotzil and Tzetzal inhabitants as non-existent political actors, unworthy of acknowledgment. Prior to 1994, it was common for indigenous people to cross the street when walking by or near caxlanes. Institutions and businesses were off-limits to the Tzotzil and Tzetzal inhabitants. They were indeed viewed as a “people without a history.” The march culminated with the tearing down of the Diego de Mazariegos statue that stood tall in the center of the city, commemorating the so-called founder of San Cristobal de Las Casas. In 1978, the town of San Cristobal celebrated its four hundred fifty year anniversary. A series of celebrations and commemorations were planned throughout the highlands town culminating in the erection of the Mazariegos statue. The statue was commissioned by coletos, the landed elites, honoring Mazariegos. For fourteen years, the statue stood near the town-square as a tourist photo-op and landing spot for pigeons. Why after 450 years was it important to commemorate Diego de Mazariegos? What did it mean to commission a statue depicting him as the founder of the colonial town, in a predominantly indigenous region? Michel Rolph Truillot would have us ask: who was erased by the erection of the statue in the late 1970s? Moreover, why did several indigenous marchers decide to climb the statue and bring it down on October 12, 1992?Some answers would come on January 1, 1994, when an army of indigenous rebels calling themselves the Ejercito Zapatista Liberacion Nacional (EZLN) declared war on the Mexican government.

El Despertador: The “Ya Basta!” Moment

I was in my last semester of high school when several hundred armed Mayan rebels calling themselves the EZLN (Ejercito Zapatista Liberacion Nacional) or Zapatistas, declared war against the Mexican government and took over seven municipalities and dozens of towns in the southeastern state of Chiapas, Mexico . The Spanish-language news media replayed the few reports and interviews on the uprising during the evening news right before the mind-controlling and captivating novelas my parents and relatives watched daily to relax from a long day of work. The images of the uprising were of a criminal band of ski-masked guerrillas or delinquents who were breaking the law and destroying public buildings in the process. Even the New York Times had a small article with very little detail on what many would argue was the first revolution of the 21st century.

The Mexican and international press focused most of their attention on the unprecedented signing of NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement), a free trade treaty between the United States, Mexico, and Canada that would open the borders to the free flow of commerce between these three North American countries. Mexican intellectual, Gustavo Esteva explains it as follows:

One very important point, though, is a question of luck. In the first week of 1994, nothing happened in the world. Not a plane crashed, no tsunami came. No princess died. No president had any sexual escapade. Nothing happened on earth. The media was empty. They had nothing to present us. So, on January 2, we had a thousand journalists in San Cristobal. CNN was projecting Zapatistas.

For economists and politicians focused on the tri-lateral agreement, NAFTA was Mexico’s long awaited entry into the global (economic) community. The country’s apparent political and economic stability were key indicators to international observers that the business-minded president of Mexico, Carlos Salinas de Gortari had prepared Mexico for its transition into the neoliberal era. Mexico was to become the model for other developing countries entering into the global economy. But as the days after the uprising unveiled, the news of an indigenous armed uprising did travel across Mexico and the world.

The poorly armed Mayan indigenous rebels caught the Mexican army by surprise on the first few days after the new year. Fierce fighting in the cobble-stone streets of San Cristobal de las Casas and other towns throughout Chiapas between EZLN rebels and Mexican soldiers ended in many rebel casualties. As the Mexican army gained military control of the situation, an immediate response by national and international human rights groups, leftist organizations and collectives from every corner of the world, as well as concerned Mexican citizens from throughout Mexico demanded a cease-fire and began arriving in solidarity with the Mayan rebels.

At that point, Zapatismo appeared in my Chicano history classroom in the form of a communiqué, El Despertador Mexicano, brought to us by three Chicana college tutors who were politically involved in the NAFTA protests across the Bay Area. The communiqué stated:

Mexicans: workers, campesinos, students, honest professionals, Chicanos, and progressives of other countries: We have begun the struggle that is necessary to meet the demands that never have been met by the Mexican State: work, land, shelter, food, health care, education, independence, freedom, democracy, justice and peace.

For hundreds of years we have been asking for and believing in promises that were never kept. We were always told to be patient and to wait for better times. They told us to be prudent, that the future would be different. But we see now that this isn’t true. Everything is the same or worse now than when our grandparents and parents lived. Our people are still dying from hunger and curable diseases, and live with ignorance, illiteracy and lack of culture. And we realize that if we don’t fight, our children can expect the same. And it is not fair.

Necessity brought us together, and we said “Enough!” We no longer have the time or the will to wait for others to solve our problems. We have organized ourselves and we have decided to demand what is ours, taking up arms in the same way that the finest children of the Mexican people have done throughout our history.

We have entered into combat against the Federal Army and other repressive forces: there are millions of us Mexicans willing to live for our country or die for freedom in this war. This war is necessary for all the poor, exploited and miserable people of Mexico, and we will not stop until we achieve our goals.

We call on all of you to join our movement because the enemies we face, the rich and the State, are cruel and inhuman. They will put no limit on their bloody instinct to destroy us. It is necessary to struggle on all fronts and from there, with your sympathy, your solidarity, the dissemination that you give our cause, your adoption of the ideals that we are demanding, your incorporation of the Revolution by raising up your people wherever they may be found, these are very important factors in our final triumph. (Zapatistas, December 31, 1993)

My classmates and I read the declaration as if it was poetry. As activists in our high school and community, we were excited to learn that indigenous Mayans had taken up arms against the injustices they faced. That their existence as indigenous people, did not figure only in Mexico’s past but part of its present. We compared the Zapatista rebellion to the 1910-1917 Zapatistas we read about in our Chicano history class. The invoking of Mexican revolutionary figure, General Emiliano Zapata, himself of indigenous descent, transcended borders as a symbol of resistance for Chicanos and indigenous Zapastistas. Weeks later we received the background we were awaiting with another Zapatista communiqué, Chiapas: The Southeast in Two Winds, a Storm and a Prophecy, written years before the uprising but introduced three weeks after.

The Chiapas communiqué spoke to the years, decades, and centuries of exploitation faced by indigenous communities in Chiapas. It laid out the contradictions of Mexico’s entrance into the global economic community. Although the ecologically diverse state of Chiapas was rich in natural resources and supplies the country with oil, water, and electric energy, it also had the dubious distinction of having one of the poorest populations in Mexico. The communiqué shed light on the inequalities facing Mayans in Chiapas and the effects NAFTA and neoliberal reforms would have on rural peasants and Indians throughout Mexico. They became a forecast for the political, social, and economic woes Mexico would face beginning in 1995 with the devaluation of the currency and the Mexican stock market crash.

The Zapatistas early communiqués resonated with the intense student activism I participated in during my senior year in high school. The “Ya Basta!” (Enough!) so often used to identify the Zapatista struggle, made sense to me and many of my classmates in terms of the educational inequity we faced in the Berkeley’s public schools. Protesting a high push-out rate of Chicano students, the attacks on immigrant students, and the constant gang profiling of Latinos at our school, we organized several successful walk-outs and protests in coordination with public high schools throughout the Bay Area. The Zapatista rebellion was used often as a reference point when we were told that Chicano and Latino students should not protest and question the social injustices facing youth of color in the Bay Area.

Moreover, it was important for the Zapatistas to include Chicanos in their the initial call for solidarity. It helps us ask after twenty-five years, how did the Zapatistas know about Chicanos? What did they know? And would Chicanos take up the call? These questions led to what I argue was the first stage of Zapatista-inspired Chicana/o activism, the solidarity stage.

Chicana/o Solidarity

Chicana and Chicano activists have been present in their solidarity with the EZLN since the initial uprising. Many went to Chiapas as soon as they heard about the uprising to serve as peace observers in an extremely tense situation between the Zapatista insurgents and the Mexican military. As long-time activist Roberto Flores of the Eastside CAFE in El Sereno, California recalled:

Right after we heard about the uprising, the so-called progressive Chicano politicians started organizing a human rights delegation to Chiapas. I included myself in the delegation even though they wondered who I was. Some of them knew me from other circles, but for the most part they were there to be human rights observers and gain political capital with progressives in Los Angeles. Their mentality was “Oh, poor Indians. We have to help them and protect them.” I went right after fifteen years of working with the league. That structure was vertical and centralized. And so when I saw Zapatismo it resonated with the rest of my life, it resonated with what I was struggling for. It resonated with all the struggles. And the ones I mention are just a few of the many, many struggles that we were going through. And I was with others that we always sought horizontality and that the organization or the party were not enough nor did they represent our desires. And it resonated with our belief in local autonomy, the respect for our conditions. And so when the Zapatista uprising came it was a breath of fresh air, an amazing thing, and so I needed to be there. I needed to be there right away.

Roberto’s recollection is crucial. It maps a shift in Chicana/o political consciousness, one that directly challenged the vertical structure of organizing within many Chicana/o political organizations. Although the Zapatistas themselves were structured vertically in terms of their military ranks, it was their regional and community organizing based on horizontal structures that captivated many Chicana and Chicano activists. This tendency towards horizontalism is a central component of what would develop as Chicana/o urban Zapatismo.

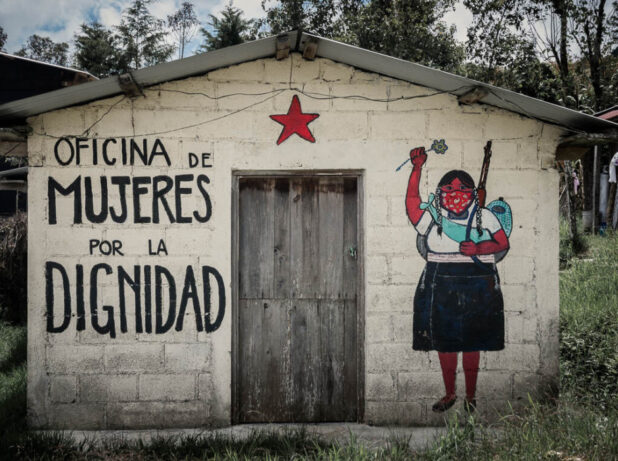

The Zapatistas quickly became a revolutionary icon amongst Leftist organizers across the world through their mestizo spokesperson, Sub-Comandante Marcos. The poetic nature of his communiques brought attention to the development of a Zapatista political ethos, or Zapatismo. Other central figures, like Mayan elder, Comandanta Ramona, represented the important role Zapatista women had and continue to have in the armed struggle. While the participation of women in guerrilla warfare is not new, considering women’s participation in armed struggle throughout Central America and Latin America, the ways in which indigenous women were challenging patriarchy and violence in their own communities inspired Chicanas in the United States. Important documents like the Zapatista Women’s revolutionary laws were another source of inspiration and political study for Chicanas and Chicanos in the United States. These laws helped usher in necessary political spaces and dialogue in Mayan communities directed at restructuring power relations in Zapatista communities.

As the Zapatista struggle turned from a peace process with Mexican officials to one of facilitating what they called “encuentros” or encounters centered on ending neoliberal capitalism, the participation of Chicanas/os meant facilitating face-to-face engagements between Zapatista communities and Chicana/o activists. For instance, Chicana/o participation in the Zapatista organized, First Intercontinental Encounter Against Neoliberalism and for Humanity, led to an important shift and critique of international solidarity. Chicanas/os from the United States started solidarity organizations that not only sent supplies and resources to Zapatista communities in Chiapas but also protested in front of Mexican embassies in the United States. Chicanas/os protested in front of embassies demanding justice for the families and those massacred in Acteal in 1997. They also noticed that the transnational solidarity movement grew predominantly white and Mexican from Mexico. This dynamic often left Chicanas/os without a space to build their organizing efforts on more than just a platform of solidarity.

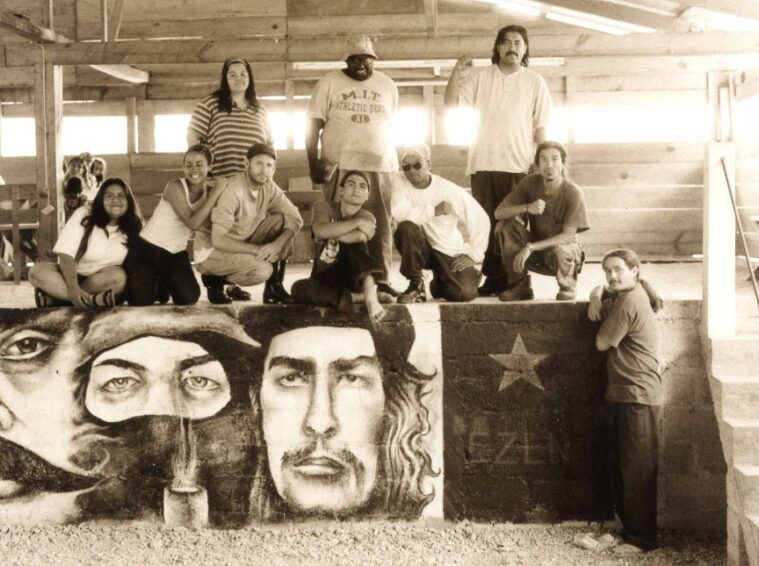

The building of solidarity, the critique of the solidarity movement, and the need to organize from the inspiration gained by the Zapatista struggle led to one of the most important shifts in Chicano/Zapatista relations. In August 1997, Big Frente Zapatista, out of Los Angeles, California, organized an encounter between over two hundred Chicana/o students, artists, and activists and the Zapatista communities of the Los Altos region of Chiapas. For a week, Chicana/o activists, artists, and musicians participated in workshops with Zapatista community members on topics ranging from autonomy to the role of women in the struggle. Each workshop resulted in a cultural collaboration between the participants. Skits, musical performances, and murals were created throughout the Zapatista political center of Oventik in the highlands region of Chiapas, Mexico. The result of such an encounter led to the answer the Zapatistas were often asked: “How do we help the Zapatista struggle?” Their response was to “organize in your communities.” The First Chicano/Zapatista Encounter Against Neoliberalism and for Humanity took this proposal very seriously. It became the watershed moment that led to the second stage of Chicana/o Zapatismo: the building of autonomy in Chicana/o and Latinx barrios throughout the United States.

Zapatista-inspired Chicana/o Autonomy and Autonomous Organizing

My first face-to-face encounter with the Zapatistas came in 1998. I participated in a peace delegation facilitated by a U.S. “people of color” collective called Estacion Libre. The collective emerged out of discussions from the 1997 Chicano/Zapatista encuentro and the widely understood sentiment that there needed to be a greater relationship between Black, Chicano, Asian American, and Native American peoples from the United States and Canada with the Zapatistas. Estacion Libre was also a response to the predominantly white and Mexican nature of solidarity groups in Chiapas. The original thought was that Estacion Libre could be a physical space in San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas for “people of color” to meet and dialogue over the impact of neoliberal white supremacy and capitalism on the lives of communities of color. The intention was also to build bridges with the Zapatista communities through peace and work brigades.

I participated as a college student in the first of these delegations in 1998. It was a life changing experience. Having conversations with activists and organizers from the U.S. over a forming “people of color” political identity and complimenting those conversations with our meetings with Zapatista communities sparked a rejuvenated sense of social justice and political organizing. After the delegation I became more and more involved in Estacion Libre. I spent summers and winters in Chiapas from 2000-2008, facilitating delegations and working with Estacion Libre coordinators in Chiapas, Mexico. By 2008, Estacion Libre had brought hundreds of activists, artists, community members of color from the United States and Canada to Chiapas to engage with the Zapatistas in meaningful ways. I noticed throughout my time in Estacion Libre, the large number of Chicana/o participants in delegations. This spurred my intellectual curiosity and it became the focus of my dissertation in Anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin. Having made valuable friendships and connections through Estacion Libre, I conducted ethnographic fieldwork on Chicana/o autonomous organizing inspired by Zapatismo.

Autonomia es Vida

Autonomy is life. For Chicanas/os, its previous articulation is self-determination, a political and cultural path that contested decades of discrimination and proposed instead a cultural politics embedded in community rejuvenation and direct-action. This previous articulation stemming from what we commonly know as the Chicano Movement did not translate completely to a new generation of Chicana/o activists and cultural producers that spoke of their own sense of “loneliness and despair” that previous generations contested. The 1992 “500 years of resistance” protests and the Zapatistas “Ya Basta!” moment was one of many that led to a recomposition of struggle in barrios throughout the United States. Instead of self-determination, Chicanas/os theorized what autonomy would mean in their communities. The move here was not to replicate Zapatista autonomy but instead learn from and find resonance in Zapatismo. The 1997 encuentro between Chicanas/os and the Zapatistas ushered in what I refer to as Chicana/o urban Zapatismo.

Following the political trajectory set forth by John Holloway, I offer the concept of Chicana/o urban Zapatismo as a way to highlight the specificity of Zapatista-inspired Chicana/o and Latina/o activism, art, music, and community organizing in places like Los Angeles. I use Los Angeles, California as my point of reference for Chicana/o urban Zapatismo primarily due to keeping with the continuities of the 1997 Chicano/Zapatista encuentro. The term offers insights into the diverse and creative organizing styles produced by Chicanas/os that are focused on furthering direct democracy, horizontal consensus decision-making models, collective practices of mutuality and reciprocity, and the building of trans-local, regional, national, and global networks.

Chicana/o urban Zapatismo contextualizes the political and cultural response, grito, and vision of a particular community composed of many communities throughout the Greater Los Angeles Area. The transition of this region into a “Latino Metropolis”, a majority racialized immigrant Mexican and Latino population, produced new political subjectivities forged from transnational processes of migration and the re-territorialization of groups into urban barrios and enclaves. The end result of this transnational imaginary redefines what a Chicana or Chicano identity means in the city. Countless youth, in particular, the recently arrived migrants to the United States, are disrupting prior notions of Mexican American identity that would have one choose between “the Mexican” or “the American” and instead re-conceptualizing their identity as “both/and,” which is inclusive of difference, flexible, and a fluid form of identity formation.

I use Chicana/o urban Zapatismo to focus on Chicana/o and Latina/o activists, artists, musicians, community organizers, educators, farmers, vendors, etc. who are inspired by Zapatismo as a political and cultural politics, but who also participate in a locally grounded political process that contests the structural mechanisms that produce a sense of “hopelessness,” “despair,” “loneliness,” and “fear” so commonly felt by youth of color during the 1980s and 1990s in Los Angeles. This distinguishes Chicana/o urban Zapatismo from other forms of urban Zapatismo because what resonates so clearly from the Zapatistas is their critique of neoliberal capitalism and racism, among other –isms, that other urban Zapatista projects might not necessarily thread in as their organizing principle. By contesting the power relations that produce social inequalities in the barrios of Los Angeles, Chicana/o urban Zapatistas are attempting to craft alternatives to the sentiments of “hopelessness” and “despair” that grew exponentially during the 1980s. This has led to the production of new and innovative terrains of struggle that are not based on a specific identity politics, but instead on a politics that threads many issues and concerns simultaneously.

This is a crucial step in the evolution of a Chicana/o urban Zapatista politics, a politics that attempts to be as fluid and flexible as possible, since it opens the doors to a plurality of experiences and approaches that each have their own alternatives and visions of what type of Los Angeles they want to create. The emergence of a renewed Chicana/o cultural scene inspired by the Zapatistas and the participation of Chicanas within Chicana/o urban Zapatismo offers a unique case study to the cultural politics that are produced through Chicana/o urban Zapatismo.

Zapatista-inspired Chicana/o Cultural Production

The political resonance of the Zapatistas in Los Angeles is symbolic of an emergent Chicana/o art and music scene in Los Angeles. Zapatista-inspired Chicana/o and Latina/o artists, musicians, and musical groups in particular have been at the forefront of this scene in Los Angeles. Since their interest in the Zapatistas began after the January 1, 1994 uprising, Chicana/o artists, musicians, and musical groups have supported and in some cases initiated Zapatista solidarity efforts in Los Angeles, California. This has not gone unnoticed by the Zapatistas or their spokesperson, Sup-comandante Marcos, who in several communiqués has thanked such groups as Rage Against the Machine, Aztlan Underground, Quetzal, and Ozomatli. Stemming from face-to-face encounters with Zapatista communities, many of these artists, muralists, and musicians have found a creative resonance in Zapatismo through their lyrical and poetic communiqués, communications, letters, and political actions. As one Chicana artist who uses the Zapatistas in her paintings reminded me, “some of the most intense poetry that spoke to me as a young Chicana came from the compas in Chiapas. The Zapatistas made it creative to be creative, if that makes any sense.” In this case, Chicana/o urban Zapatismo’s connection to the arts, music, and creative forms of expression is this new vocabulary coming from Chicana/o youth who feel that prior cultural movements like the 1960s Chicano movement had grown stale and tired with internal political battles over power, dogmatic views over political organizing strategies, hierarchical methods of structuring movements, and isolating male-centered identity politics that are ethnocentric, sexist, and homophobic.

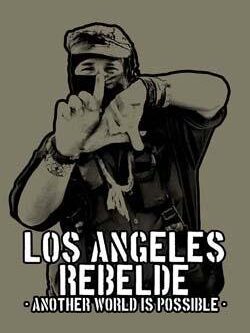

Muralists and Graffiti writers, like the Los Angeles native, Nuke, traveled to Chiapas and worked on several murals in San Cristobal de las Casas and in Zapatista communities, including collaborative mural projects in the Aguascalientes (early Zapatista political and cultural centers) of Oventik and Morelia. Although not Chicana, Alicia Siu, an indigenous Central American muralist, who participated in Estacion Libre delegations to Chiapas, Mexico, paints murals and art pieces dedicated at reestablishing an indigenous connection to struggle and land across the continent. Her pieces also focus on the trauma of war and violence in Central America. Other contemporary artists like Oscar Magallanes, who also traveled to Chiapas as part of peace delegations and found the encounters with the Zapatista communities life changing and transformative. Oscar, an artist who works with wood instead of canvas, attended an Estación Libre delegation to Chiapas in 2005. Oscar was inspired by many of the images he saw during the delegation and having the opportunity to witness first-hand Zapatista autonomy and autonomous organizing and the use of art within Zapatista communities. They reflected his own depictions of working-class dignity in the everyday lives of day laborers, fruit stand owners, ice cream vendors, and farm workers. According to Oscar, “Most of my art is about the Los Angeles everyone forgets. It’s about the people forgotten. Un Los Angeles rebelde y digno. It’s also about love and dreams. Because these people are often left without dreams or love.” Both Nuke and Oscar are representative of a grounded cultural politics and through their art they are making certain histories and experiences visible to broader audiences and communities.

Marisol Torres also uses multiple mediums, including canvas, print, wood, and paper mache, as her artistic expression. Marisol is a member of a number of Zapatista-inspired collectives in Los Angeles and an active member of the Xicana/indigena women’s multimedia group, Mujeres de Maiz; co-founder of the comedy theatre group Chusma; the women’s performance group, Las Ramonas; and a member of the women’s drumming group, In Lak Ech. She is also a native of East Los Angeles and one of the original members of Big Frente Zapatista which coordinated the 1997 Zapatista/Chicano cultural encounter in Chiapas, Mexico. Like Oscar, Marisol uses images that capture the everyday life of native women and men. She uses Zapatista images and dichos in her paintings and sculptures. Many of these paintings, prints, and sculptures are sold only at other Zapatista-inspired events like the El Puente Hacia La Esperanza “Anti-Mall.”

Most Zapatista-inspired artists and musicians incorporate popular education as part of their cultural expression. Many of them are teachers, mentors, tutors, or work in fields related to education or social services, where they work directly with populations that are in desperate need of resources and help. This inherently shapes their politics and their cultural production as artists and musicians. For instance, Martha Gonzalez and Quetzal Flores, members of the Chicano musical group Quetzal, have taught traditional dance, music writing, and musical instrument classes to elementary level children, high school youth, and university students. Martha Gonzalez, who is an associate professor at Scripts College, offers song workshops not only to her students but also inside women’s prisons in Arizona.

The teaching of traditional art and music is also a key facet of Chicana/o urban Zapatistas cultural production and identity formation. Musical groups such as Quetzal, Ozomatli, Quinto Sol, and Aztlan Underground, take their group names after indigenous names. Stemming from a long tradition of cultural identity recuperation, these musical groups are continuing the reaffirmation process that began during the Chicano movement of the 1960s and 1970s in Los Angeles. While during the Chicano movement, embracing an indigenous past fueled the cultural renaissance of the movement and cemented a Chicano political identity, a political connection to contemporary indigenous cultures and communities informs the day-to-day interaction with new transnational indigenous communities that have made Los Angeles their home and a hemispheric connection between Chicana/o artists, activists, and musicians with indigenous and Afro-Latin groups throughout the Americas. These two processes of acknowledging the past and identifying with the present, has expanded the political and cultural meanings of a Chicana/o identity. The difference in the latter is that one’s politics is the basis of engagement and encounter not a perceived ethnic connection or past.

Besides redefining a Chicana/o identity, these art and music groups are also collaborating with each other through city-wide gigs where they perform side by side, offering each other support and expanding the cultural scene by offering a cultural experience that is made up of many sounds and artistic mediums. As Victor Viesca argues, compilation albums between Chicano musical groups not only provide a snapshot milieu of the musical scene but also demonstrate the collective nature of these groups and the politics embedded in their music and in their interpersonal relationships. This has resulted in Chicana/o urban Zapatista art and music groups creating their own art collectives, spaces, studios, and record labels. Such multimedia collectives as Xicano Records and Films, created by members of the Chicano band, Aztlan Underground, include filmmakers and musicians that capture the essence of this cultural scene in Los Angeles.

The politics of the emerging art and music scene also corresponds to the relationship between Zapatista-inspired artists and musicians and their conscious effort to engage their audiences through art and music. Basing their critiques on a cultural production that has become “voiceless,” “apolitical,” “corporate,” and “elitist,” these artists and musicians attempt to make their craft accessible and real to their target audience. For example, Olmeca, a solo hip hop MC, uses his music as a way to invite his audiences into an encounter with each other. Olmeca facilitates and participates in discussions with his audiences not only through his music but also with a concerted effort at working politically and culturally with the groups, collectives, and places he visits and performs. Olmeca talks about his relationship with his audiences in this way:

I learned from the EZ that we can create encuentros everywhere. That not only are the audiences listening to my music, seeing themselves in the lyrics, joining me in some form of rebellion, but they are also asked to participate after in an encuentro. So they can meet each other and talk to each other. At first, I had people be like, I came for a show, I didn’t come to talk or to meet people, but then we started meeting and people expressed their anger and hopes, and they started organizing with each other…I travel all over the place and in each place that is a big part, the process, the encuentro.

Olmeca, who went solo after years working with bands such as Slowrider, grew up in East Los Angeles. For Olmeca, Zapatismo is directly connected to the experiences of ethnic Mexicans and people of color in Los Angeles because it accentuates the creativity and vast spectrum of expressions within Mexican Los Angeles that according to him, “is an art”, “an act of rebellion” that allows disenfranchised groups to find common ground in their difference. His experiences are different than many Zapatista-inspired Chicana/o musicians and artists. Having one foot in Mexico and the other in East Los Angeles places Olmeca in the middle of two distinct worlds and experiences. Tying the lives of Mexicans in Mexico and those of immigrants and people of color in Los Angeles, California has been a major part of Olmeca’s current musical production. According to Olmeca:

We are all different. It’s not like we are competing with our music. It’s about bridging them. Remembering those that came before and connecting with those who are playing now. It’s like, how can I explain it? I take from my personal, family, and communities experiences. They are always in my music. I like putting them in conversation even if they don’t talk to each other sometimes. I like putting my Mom and Dad in conversation with those minutemen racists and see how hypocritical and racist these groups can be to my parents who are talking about just living and working…I put the activist who comes and gives a dope talk to fools like me, in conversation with youth like me when I was young so that the activist can see that we got something to say too. That comes out in my music and lyrics. It’s a challenge but that is part of Zapatismo. The challenge.

This politics of bridging experiences is similar to what the Xicana/indigena drumming group, In Lak Ech, suggest through their group name. As Felicia, one of the collective members, comments:

In Lak Ech, is Maya for, “tu eres mi otro yo.” It speaks to our many dualities and reflections that each of us are to one another. When we treat each other like this, in an interconnected way, we are obligated to walk with each other because we are a reflection of each other…No pos, how many times do we go about our daily lives not seeing each other in others. Our colectiva of mujeristas wants our native ways and songs to reflect our realities and our ancestors. Past, present, and futuro.

Zapatista-inspired Chicana/o artists and musicians are embracing the very meanings of the saying, In Lak Ech, in their art and in their music, but most of all in their relationship with their audiences and with the different communities with whom they identify.

Chicana urban Zapatismo

At the forefront of Chicana/o urban Zapatismo in Los Angeles is the role Chicanas, Latinas, and other Women of color play within collectives, organizations, spaces, and art circles. Resisting the effects of neoliberal capitalism, white supremacy, patriarchy and homophobia on the lives of women of color and critiquing the internal organization politics and a lack of gender analysis within movements, Chicana urban Zapatismo emerges as a crucial and binding terrain of struggle within Chicana/o urban Zapatismo. Their role within Zapatista-inspired activism, art, music, and community organizing is a reminder to Chicano urban Zapatistas that building autonomy is susceptible to the same power differences that their Chicano movement predecessors found to be fragmenting.

Chicanas were quick to identify with the Zapatistas shortly after the Zapatista uprising. Images of Zapatista indigenous women soldiers, having important leadership positions within the uprising, initially inspired Chicanas and Latinas with a renewed sense of revolutionary fervor, not witnessed since the Central American guerrilla groups of the 1980s. Moreover, spokespersons such as the Zapatista Comandanta Ramona, a petite Indigenous elder who was responsible for the takeover of San Cristobal de las Casas, became iconic figures for women throughout the globe.

As the world became more and more aware of the Zapatista model of including women within their military ranks and within their civilian decision making structure, Chicanas found resonance in Zapatista women’s response to centuries of male-patriarchal power in their daily lives. The Zapatistas, unlike other revolutionary groups, incorporated these important critiques by women into their organizing with the “Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Laws,” but not without a fight from many Zapatista men. Chicanas saw the revolutionary laws as an attempt by Zapatista women to dismantle the patriarchal structure of their daily lives. It reinforced their own desires to create communities and pursue an autonomy that included the dreams, visions, and participation of women without the oppressive restraints of hetero-normative patriarchy. Mixpe, a Chicana feminist artist, and part of the Chicana performance troop, Las Ramonas, discusses this point in greater detail:

What good is autonomy, if we as mujeres are still talked over in meetings, or not seen as doing anything. When I worked in the Zapatista Caracol of Morelia, I worked with the mujeres in the community, on projects. I asked them how things had changed since the uprising. They used to tell me, “We [as women] have a greater say in things. We aren’t left out. If one of us gets golpeada (battered) by our husbands, we don’t have to be quiet.” When they would tell me this, I used to think of how we treat each other in LA. How we treat each other at meetings, or at events, or even on a personal level. That is one of the biggest issues in our comunidad, domestic violence, against mujeres, our elders, our young. There is a lot we can learn from the Zapatistas, but we shouldn’t have to go thousands of miles to see where we need to change. I used to be hard core about calling out men, and it’s not like I still don’t but now we’ve developed as mujeres different ways of confronting men and women on their shit. We now have reflection as part of our process…This, I always think of as autonomy.

For Mixpe, a strong criticism of how Chicana/o organizations and collectives continue to be dominated by men and recreate forms of internal violence that eventually fragment social struggles is a reminder that women are attempting to transform the nature of these spaces through methods and processes that both confront these power dynamics at their core but also situate a politics of reflection as a crucial aspect of organizing towards autonomy.

Diana, a Chicana lesbian artist living in Highland Park who attended one of Estación Libre’s people of color delegations to Zapatista communities, shares Mixpe’s analysis and adds her experience as a queer Chicana:

Part of what my art speaks to is the response to the heteronormative values that our gente believe strongly in. My arte shows the other side, the side that isn’t talked about at our dinner tables or our political meetings because it makes men and women uncomfortable…the Zapatistas spoke to me because of their rebel hearts, their spirit that breaks so many barriers but I’m not naïve, I know they have their pleitos…I always wonder whether after the Zapatistas came out, if indigenous women and men also came out. On the delegation that I went on…I asked the compas whether queer compas were free to come out and if they were accepted. They kinda looked at me like they didn’t understand the question and I looked at the people of color on the delegation and they kinda looked at me the same. But I asked again, “y que lugar tienen las mujeres y hombres que son gay?” They were like, “Si, ellos tienen lugar, pero no tenemos en esta comunidad gente gay.” I wanted to follow up and say, “How do you know?” but I refrained. I think their response spoke a lot to me because it showed me to not romanticize a struggle but see it as a long process that we must all travel if we believe in social justice.

Chicana urban Zapatistas like Mixpe and Diana are de-romanticizing the Zapatistas as the model to emulate and follow. They are demanding that Chicanas and Chicanos who are working on social justice chart their own path and process, while along the way, reflecting on each step taken as part of that “long process.”

Besides attempting to change the dynamics within political organizations and collectives, Chicana urban Zapatistas have also created their own autonomous spaces to pursue their art, music, activism, and spiritual energies. Oftentimes, chastised by men for building their own spaces to discuss issues facing women, these Chicanas offer Chicana/o urban Zapatismo an example of how to build autonomy and self-determination with very little resources. Important to building these autonomous spaces is the construction of social networks that reach out not only across neighborhoods or regions but connect with other radical women networks across the globe. For instance, La Red Xikana Indigena, is a network of Chicana and indigenous women throughout the Americas that work on issues of human rights for indigenous women and communities by lobbying the United Nations for indigenous rights throughout the globe. Other collectives and networks include Women Image Makers, a collective of women who work on multimedia, audio, and video production with a focus on women, youth, community building, and Queer LGBT groups.

Such multimedia groups like Mujeres de Maiz for instance are collectives of women artists, poets, filmmakers, photographers, writers, workers, mothers, sisters, grandmothers, who have different levels of education and come from different life experiences. Each member of Mujeres de Maiz connects her different experiences and social networks with other members to produce an expanding network of women cultural workers who are using their art as an “educational tool for resistance, healing, and change.” Founded by Felicia Montes and Claudia Mercado, the Mujeres de Maiz collective, for instance, was formed in 1997 out of the Zapatista-inspired organizing space, the Popular Resource Center/Centro de Regeneración.

Connected with the Mujeres de Maiz collective, the Chicana music and poetry group, In Lak Ech, provides audiences a spiritual activism that is often neglected and overlooked by organizations. By offering Chicana Indigena songs and drumming, In Lak Ech is breaking gender specific roles that prefigure men as fulfilling the roll of traditional indigenous drummers. Their music is both inspiring to young women who also perform musically throughout Los Angeles and a metaphysical autonomous space to heal and regenerate from the many wounds and battles women encounter in their daily life. In Lak Ech is also a spoken word collective that uses the Zapatista slogan of “our word is our weapon” to share the cultural sensibilities and hopes of Chicana indigena womyn in Los Angeles with audiences across the country.

Chicana urban Zapatismo is an important facet of Chicana/o urban Zapatismo in Los Angeles. It fissures a politics that is not only focused on centering Chicanas and other women of color within oftentimes male-centered spaces. It also understands autonomy and the pursuit of autonomous spaces as a valuable source of transformation and reflection for Chicanas to organize out of. In turn, Chicana urban Zapatismo makes clear and innovative political and cultural contributions that critique racist and sexist tendencies within Chicano/Mexicano/Latino culture and US society as a whole.

The Zapatista Legacy and the Continued Resistance

Chicanas/os/x in the United States, like their historical counterparts in Mexico, are at a watershed moment. In the United States, Chicanas/os/x face a series of internal and broader societal issues and concerns that should result in the recomposition of what it means to be Chicana/o/x. Like the 1992 and 1994 moment, what it means to be Chicana/o/x has shifted and changed to be critical of our recent past and persistent in our battle against the production of a “people without a history.” It offers us an opportunity to acknowledge and build an interconnected relationship with others with similar but distinct experiences and to walk carefully not to reproduce the power relations of previous generations. If the many headed hydra appears to us as a wall, a dam, as the Zapatistas have analyzed, then what tools do Chicanas/os/x use to make cracks on the wall? Are we hesitant to join others who also pound on the wall or will we be brave in our “Ya Basta!”

Similarly, in Mexico, the election of Alvaro Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), is being lauded as the “fourth transformation” in Mexican history. The politics of history and the social co-production of a “people without a history” has rearranged our “other calendars” of the past to see this AMLO moment as an erasure of January 1, 1994 and the twenty-five years of Zapatista and indigenous struggle. The Zapatista analysis of political power rings even louder today. AMLO and Morena have shown themselves to be wolves in sheep clothing. Whether one disagrees or not with the Zapatista position on the current AMLO moment, the Zapatistas and the CNI deserve attention. Those that once supported the Zapatistas, alongside the Congreso Nacional Indigena (CNI), are now turning a blind eye. Some are going so far as to argue that the Zapatistas are an antagonist and thorn in the side of progress. Veiling the anti-indigenous nature of their claims, some have accused the Zapatistas of abandoning them at a moment of victory. I continue to align myself with the Zapatistas, as the Z’s would say: “no les pedimos permiso a nadie.” Indigenous resistance is predicated on this sense of not asking for permission. And yet, the Zapatistas continue to be a beacon of light and hope for us all.

And what of the Mazariegos statue? Sub-Comandante Insurgente Galeano would answer that for us twenty-three years after the October 12, 1992 protest:

Many years ago, we Zapatistas did not march, or chant slogans, or raise banners or even our fists. Until one day, we did march. The date: October 12, 1992, when those above celebrated 500 years of “the meeting of the two worlds.” The place: San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico. Instead of banners we carried bows and arrows, and a deafening silence was our slogan.

Without a lot of noise, the statue of the conquistador fell. If they put it up again it didn’t matter. Because they will never again be able to put back up the fear of what it represented.

Much like the symbolic nature of the San Cristobal Mazariegos statue that was toppled in 1992, Chicana/o/x activism has been forever altered. We as Chicana/o/x activist must continue to move forward and continue to build across borders, across colonial nationalistic identities, and for a world where many worlds can exist.

Revista N’OJ ©<script>document.write( new Date().getFullYear() );</script> All right reserved.