FOR THE LATINX RESEARCH CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY

RIGHT ON! AN INTERVIEW WITH RUPERT GARCIA

By Mauricio Barros de Castro

I met Rupert Garcia at a restaurant in Oakland, the city where he lives. I had no doubt that I was going to interview a legend of Chicano Art. During the 1960s and 1970s, he participated actively in the civil rights movements in the Bay Area of São Francisco, CA. This period was a context marked by the Black Power movement and the Vietnam War, the destination of most youths belonging to these minorities, like García himself, sent to the battlefront in disproportionate numbers compared to the white Americans who fought in Vietnam.

Rupert Garcia was born in French Camp, California, in 1941. Artist, researcher, and recently retired tenured professor from the School of Art and Design at San Jose State University, in 1981 García completed a MA in History of Art at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1968, he decided to stop painting and make political posters that denounced the violence against Latinos, Black folks, and other minorities in the United States.

The quick and simple technique of the silkscreen, the graphic possibilities, and the poster’s immediate communication with the public, pop art in support of activism, were factors that led García to take risks and create a powerful political and artistic series.

Mauricio Barros de Castro: You were talking about a picture in the catalog of your exhibition Rupert Garcia: Rolling Thunder, presented in the Rena Bransten Gallery in 2018, and your participation in the Vietnam War.

Rupert Garcia: All right, I was just saying that the picture on the catalog from Rena Bransten Gallery has a ribbon over my eyes… the ribbon is the US government’s presentation to acknowledge that you were involved in the Vietnam War, so when I went there I hadn’t I wanted to go, but I didn’t really know why. I was anti-communist very strongly then, as most Americans were and many still are, so and that was one reason why I volunteered to go, but I didn’t know anything. When I came back, I learned that the war is a really illegal and colonialist war, but we took up. We help get rid of one of the Vietnamese presidents, but we couldn’t control that president so we had to get through. We, meaning the government, worked to get him killed and so I didn’t know any of this I learned later. So, I make a picture that I take this photograph of me when I was in Indochina, where my eyes are wide open very young man, but now I know about the Vietnam War, so I put the ribbon on my eyes. So I’m saying I know now that I was blinded to

Hoodwinked, 2017, pigmented acrylic inkjet on paper,

paper size: 36 5/8 x 30 1/4 in., image size: 29 x 25 3/4 in.,

edition of 10

go to war. It was a critical picture of-about me and the US government, but now I understand that I was blinded to go to the war. I like to do that in my pictures, and I like to make those kinds of connections that are critical and contradictory. Yeah, so this was made in 2017, the first time I’ve ever done something like this. I never- when I got out of the Vietnam war, I came home in ‘66 – I never told anybody for maybe 20 years that I was involved in the Vietnam War. I told nobody. I just kept it to myself, but it was difficult, very difficult because I became a part of the anti-Vietnam movement in the United States and throughout the world and I made a lot of images about protesting the Vietnam War, but I never told anybody that I was in there. For example, this

is 1970, so no one knows. I made this for the Chicano Moratorium for East Los Angeles in 1970. I sent them a big package of all my posters of this one, but nobody knew, nobody knew.

Mauricio Barros de Castro: How long did you spend in the war?

Rupert Garcia: One year. It was Special Duty, one year a secret airbase, and I was part of a flying bombing mission called Rolling Thunder, that was the name of it. They bombed North Vietnam, the Ho Chi Minh Trail, terrible, just terrible. This came in here; just for your information, this is a big painting on paper this is the landscape right outside of my airbase. I took a photograph over 50 years ago, and so I made a painting of this and these are the kinds of airplanes that I had to secure, had to protect and this is what these airplanes did. So this is really personal, a very personal painting. I love it, I still love it if you see it in person the colors, the way they interact, and the way the paint is put on. I just love it.

Rolling Thunder, 2017, mixed media on paper, paper size: 60 x 100 in., image size: 52 x 96 in.

So I think of myself as a painter, but from ‘68 until the mid-70s I did not paint. One time I painted I made a painting of Ruben Salazar, he was a writer for the Los Angeles Times. He was born in Mexico, came to the US, became a citizen, and he became a journalist and he started to write articles about Chicanos and Mexican Americans. Critical articles, a very popular man in his writing, and he gets shot in Los Angeles at a bar, and Ruben Salazar was here in LA for this big demonstration. He and his news people went to the Silver Dollar Bar to have a cerveza or whatever, and then the sheriffs came in and then shot tear gas, and they killed him. So, many people believe it was planned to kill him. That’s what people think.

Mauricio Barros de Castro: Because of his articles?

Rupert Garcia: Oh yeah, he was very critical, he was a very smart guy, and so in 1970 I made a painting, one of the very few I made. In ‘68 to the mid-70s, I made no paintings, but I made this one here at the Galleria De La Raza. We had a special exhibition to honor Ruben Salazar, so I made the poster for the exhibition and I made a painting for the exhibition, but after that, I didn’t paint much. I made carteles, I made that.

Rupert Garcia, 1970, Ruben Salazar Exhibition Poster for Galeria De La Raza

Mauricio Barros de Castro: Why?

Rupert Garcia: In 1968, I’m a graduate student at San Francisco State College. I’m studying painting, and in 1968 my school goes on strike, students strike. All throughout campus and it was organized by a group called Third World Liberation Front. Students de color are very important, very critical about the higher education, about a lot of things. So we had a meeting in 1968 during the strike, students and faculty, to talk “What are we going to do for the strike? How are we going to participate in the strike?”

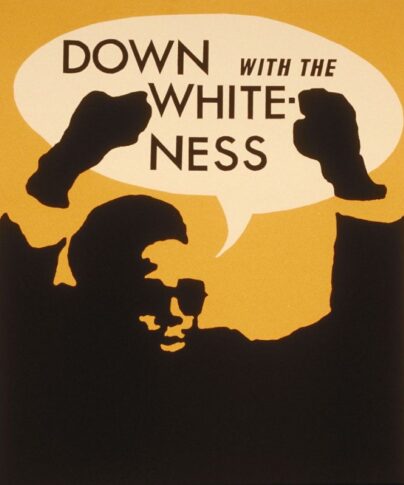

“So we heard about students in Paris May of ‘68 that they were making posters, and so at the meeting, we talked about this, and we go click-yeah-that’s the way, so I stopped painting because painting then seemed unnecessary for me. It didn’t seem necessary, the posters seemed to be what was needed to be done, and I wanted to do it.”

Rupert García, Down with the Whiteness, 1969, screenprint on white wove paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 2020.42.1, © 1969, Rupert García

So I stopped painting, and I made these posters, but then I go back to painting eventually. I didn’t stop painting just for a while. Then I continued to make posters and at the same time make paintings but at first only posters very focused. It was a political decision, very much based upon politics of the time. I mean, what is the best way to make a picture about the crisis on campus, in America, in the world? What is the best way? And the poster thing was the answer for me.

Mauricio Barros de Castro: Why were the posters the best way?

Rupert Garcia: Well, because you can make them quickly. A painting would take months, and there’s only one. Where the poster you can make many in a short time, a very short time. When I made my posters, my thinking was like a painter, like a fine artist. I didn’t change my thinking about aesthetics and design and significance. I still was thinking like I always think, as I think today. I want to make the best I can make. No matter what it is. If it’s a little drawing or if it’s a poster or if it’s a big painting or if it’s-I have done some huge murals, 17 ft by 25 ft and some a little bigger. So the thinking for doing that the poster, the painting, the drawings, and the big mosaic is the same. There’s no, because I’m doing it, so how can it be changed, no hierarchy, they’re all important to me.

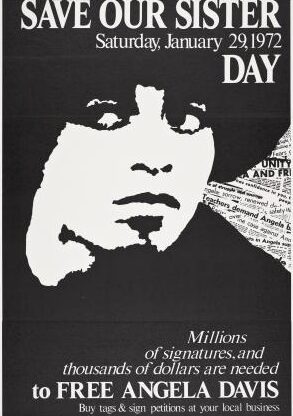

Mauricio Barros de Castro: You also made posters with some people of that time, like Angela Davis, for example.

Rupert García, ¡LIBERTAD PARA LOS PRISONEROS POLITICAS!, 1971, screenprint on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Margaret Terrazas Santos Collection, 2019.52.2, © 1971, Rupert García

Rupert Garcia: Oh yeah. Angela, when she was in trouble with the police I was in support of her critical thinking and her writings and comments about the problems in our country and in the world. Anti-racism and anti-class, so I agree with that, and when she was arrested and put in jail, I worked with the Free Angela Davis committee, and I made that poster in support, and she’s now a very good friend of mine.

Mauricio Barros de Castro: Was Chicano Art influenced by the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement?

Rupert Garcia: Yeah, it depends. In general, I will say yes. How or to what degree depends upon the individual. For some Chicano artists, they were influenced very little and some a little more so it’s a mixture there is not one response. Different kinds of responses and mine was pretty strong. I was familiar with the Black Panther Party and their main artist Emory Douglas. I always liked his work; he made the drawings for the Black Panther Paper. He made posters, and I liked them very much so I was influenced pretty strongly. I felt a strong link with that cultural response on the activist culture of the Black Panther Party.

Mauricio Barros de Castro: Pop Art was also important to you?

Rupert Garcia: Yeah Pop Art becomes important to me when I was a boy living in Stockton, California. I used to make drawings of movie stars. This is in the 1950s. I’d make drawings of movie stars and popular singers and based upon magazines, Hollywood magazine about movie stars and celebrities. My momma used to buy them, so I would make drawings of what’s in there. I was doing Pop art in the ‘50s before I knew Pop art existed. I wasn’t trying to make Pop art. I was making what’s in front of me in my life, which was these movie stars, and famous singers, and a couple of musicians too. So I didn’t know about Pop Art until after I came back from Vietnam, I learn about it in art classes and then art magazines. So I learned about it later, and I was attracted to it because some of the imagery that Pop art was making pictures of were objects that I was familiar with as a boy and as a very young man, so I was attracted to it. I also liked the Aesthetics of Pop art…some of the Pop art is very flat color, bright color, shapes were very clean and very sharp and very obvious. So I like the Aesthetics of Pop art. Then in painting pop art I really was attracted to James Rosenquist very much. He is a very good painter and the way in which his compositions are very complex but very beautiful and sometimes puzzling. Puzzle the mind and then sometimes they were critical of the United States, the bad parts of the United States. Then, Robert Indiana, I liked. And then I learned about artists in Europe in the sixties; I got me Juan Genovés from Spain. They were doing things that were kinda pop-ish, but they were more critical than American Pop art. Socially and politically, the Europeans were more critical than the Americans, some Americans were critical but they were not really hard critical.

Mauricio Barros de Castro: Which artists of the Pop arts in America do you like?

Rupert Garcia: James Rosenquist is one, his paintings in particular, and then the Warhol screen paintings of violence. He did a series on violence and some on prisoners that were very interesting, but most of his work I have no interest in. Little interest, I won’t say no, but little interest. Let’s see, who else in American did I like? Another Pop artist. Not many for different reasons. I didn’t look for political artists off the top, it’s just that some of the Pop artists in America, because of the way I was thinking, then I was thinking very critically, socially and politically critical, that’s my thinking, but I’m still interested in Beauty.

Rupert García, ¡Cesen Deportación!, 1973, reprinted in collaboration with Dignidad Rebelde 2011, screenprint on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Samuel and Blanche Koffler Acquisition Fund, 2020.39.9, © 1973, Rupert García

“If my work is not beautiful and critical, I don’t do it. It had to be both, hard to do, but I want to do it.”

Rupert García, Right On!, 1968, screenprint on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 2020.42.3, © 1968, Rupert García

I find it challenging Black life is challenging art can be challenging, and that’s what I want. So most of the American Pop artists I didn’t find them that challenging…

Mauricio Barros de Castro: And what about the silkscreen?

Rupert Garcia: 1968 when the students and our faculty had this meeting, we were talking about what are we going to do for the strike at our school, and somebody mentioned posters, and that was fantastic. Then what’re we gonna use? What’s the mechanism to make the poster? Silkscreen. What’s silks? I never heard of silkscreens before; what is that? What’re you talking about, because I’m painting, you know? One of our professors of printmaking teaches us silkscreen. I loved it. I just loved it. I love the way the ink lays down flat, beautiful. The colors are solid and very rich, and I found that very exciting, and I liked everything about silkscreen. We made stencils to stick onto the silkscreen. You had to cut it by hand with a knife, and I love that, it’s very beautiful. So the technology of silkscreen became very attractive to me, almost as much as making the design and the poster itself. So everything was important and exciting, everything.

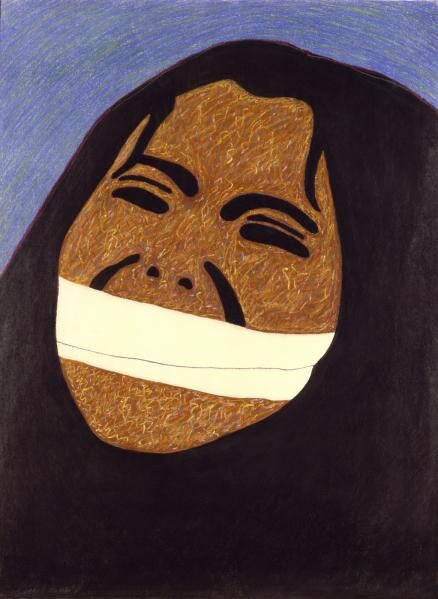

Rupert García, Political Prisoner, 1976, pastel on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Rupert García and Sammi Madison-García, 1978.107, © 1976, Rupert García

“For me everything has to be exciting otherwise I’m not interested in it. And it turns out that silkscreen was very exciting. I just fell totally in love with it. That’s all I thought about. ”

Maurício Barros de Castro

Maurício Barros de Castro, Ph.D. in History, University of São Paulo, is a professor at the Rio de Janeiro State University and currently a visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley. Castro research’s focus on the art of the Black Power movement (1963-1983), mainly Afro American artist Faith Ringgold, and its connections with the artworks of Chicano artist Rupert Garcia and Afro-Brazilian artist Abdias do Nascimento. His areas of expertise include an interdisciplinary perspective on Contemporary Art, Black Popular Culture, African Diaspora and Afro-Latinx History. He is the author of three books on Afro-Brazilian Popular Culture and is published in AM Journal of Art and Media Studies (2018) and African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal (2016).

Revista N’OJ ©<script>document.write( new Date().getFullYear() );</script> All right reserved.