FOR THE LATINX RESEARCH CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY

Opening the Bundles: Artists Creating New Realities

Through Spiritual Offerings

By Jesus Barraza

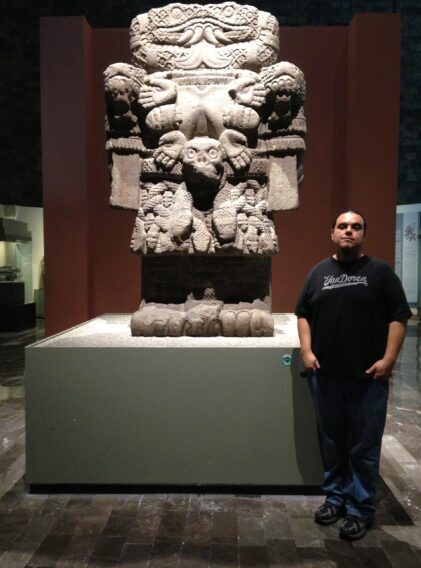

Walking through the Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, I visited with the stone ancestors of Anahuac, sculptures I’d only seen in books and on the internet. It was my second trip to the Capital and this time around I needed to see the Coatlicue statue in person. She was dug up in 1790 and was quickly reburied by the Spanish after the local Indigenous people came to worship her, afraid that she might undo what they had done. A threat to the conversion process, the mother of all creation drew her people back and gave them hope of the old world returning. The people came with offerings as they had done in the past.

Artist Unknown. Coatlicue. 1325/1521. Sculpture, 43’ x 115’ x 43″. Museo Nacional de Antropología, México.

Seeing Coatlicue on her pedestal for the first time, I considered how Xicanxs have come to see her as one of their patron saints, not necessarily replacing the Virgen de Guadalupe, but occupying the same spiritual space for many who have reconnected with their indigeneity. I also considered how it took generations for a reversal of sorts: for so long we knew Coatlicue as the Virgen, since she appeared to Juan Diego on the hill at Tepeyac in 1531, when she shapeshifted into the image we see on his tilma. By revealing herself in this form she helped in the conversion of her children by knowing in their heart they were praying to Ipalnemohuani, the mother of all life.

Original Tilma Worn by Saint Juan Diego, 1531, Pigment on Cloth, Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Tepeyac Hill, Mexico City, Mexico.

Indigenous people were persecuted by Spaniards for praying as their ancestors did, and with the appearance of la Virgen, they were able to keep their beliefs tucked away as they prayed to the Virgen they prayed to “the mother of all life.” Now, over 500 years later, those threats are gone, Indigenous people are now able to freely exercise their traditions and we are free to make our pilgrimage to Mexico City to visit Coatlicue, say our prayers at her feet, and reclaim a piece of what we’ve lost.

Reclaiming ancestral heritage is a complicated process, we have to move centuries of earth that’s been covering our history. In the midst of the forced conversion to Catholicism through destruction and violence, the Mexica secretly buried their sacred objects with hopes that they would be recovered once the Spanish went away. This is part of what Nelson Maldonado Torres refers to as a metaphysical catastrophe, where there is a “transmutation of the human, from an intersubjectively constituted node of love and understanding, to an agent of perpetual or endless war.” This endless war refers to the experience Indigenous people have faced as a result of the colonial invasion that started in 1492, and spiritual conversion was part of this violent process as people were persecuted for resisting as they tried to keep their spiritual beliefs and worldview intact. This process of war became less obvious with time as it was normalized in society and continues to plague Indigenous people today. In response to this violent treatment, there has been a desire to decolonize, to take back our lives and reconnect with what has been taken.

Decolonization is not about being seen by the colonizer, instead it is a process of redefining and recognizing one’s humanity. As Maldonado-Torres notes, decolonization “necessitates the formation of new practices and ways of thinking, as well as a new philosophy, understood decolonially, not so much as a specific discipline or way of thinking, but as the opposition to coloniality and as the affirmation of for forms of love and understanding that promote open and embodied human interrelationality.” This opposition to coloniality that affirms love and understanding is one of healing, within community and the self. As a Xicanx people we are healing from the trauma imposed by the normalization of war during the colonial period, in decolonizing we’ve recognized the harm that has been done to our people and looked for ways to heal our communities. This process led us back to the sacred bundles the ancestors left buried hundreds of years ago, they were rescued by Chicana/o artists in the 60s as they reclaimed their indigenous cultures. Patrisia Rodriguez describes bundles as “sacred technologies used to gain insight or to initiate sacred action,” in the hands of artists they become tools for transforming reality by presenting new ways of understanding the world. This role they undertook is what Gloria Anzaldúa’s Nepantleras, the “artistas/activistas (who) help us mediate these transitions, help us make the crossings, and guide us through the transformation process—a process I call conocimiento.” It is through conocimiento that artists are able to reach this interrelationality, that sense of connecting and being in relationship with the self, others, and the world as they transform the way people see the world. It is through the relationship artists form with their community through their art that they help in the process of recovering what has been lost through the centuries and in the process heal colonial traumas.

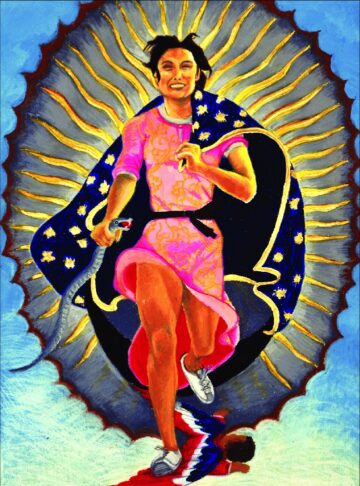

Yolanda Lopez, Margaret F. Stewart:Our Lady of Guadalupe,1978.Downloaded from www.csupomona.edu.

In the late 1970s Yolanda Lopez began a research project on the Virgen de Guadalupe, digging into her origins and story, she created a series of pieces reflecting on her findings. The most recognizable is the series of paintings of Lopez, her mother and grandmother as the Virgen de Guadalupe. These series of works are a cornerstone of Xicanx art, they are part of our heritage and ever-present in our homes, if only as postcards we frame because they remind us of our mothers. In 1982 Lopez participated in the Progress in Process exhibition at the Galeria de la Raza, where each artist was given a 4’ x 8’ masonite panel to paint throughout the run of the exhibit.

At the Galeria, Lopez painted “Nuestra Madre,” an image of Coatlicue as the Virgen de Guadalupe, or better yet, an image of Coatlicue breaking through the disguise she’s worn for so long. The image has the aura of the Guadalupana, the sun’s golden rays behind her, the black crescent moon below, covered by her midnight turquoise cape with golden stars, with her robe laying by her feet. But the Virgen morena, la Reina de las Américas, is no longer in the picture, she’s been replaced by Coatlicue de Cozcatlán the mother goddess of the Sun, the Moon and the stars.

Lopez’ painting of Coatlicue is an unraveling of the sacred bundles that the Mexica buried for another day, nearly 460 years later we were ready to unpack and reclaim those things that were denied to us for so long. Now we have la Diosas, Coatlicue and Tonantzin in our lives, the ones that protected their people through the darkness of colonization and helped them endure its dehumanizing effects.

Yolanda Lopez, Guadalupe:Victoria F. Franco,1978.Scanned from Yolanda Lopez by Karen M. Davalos.

As Xicana Indigena people, we have been able to recover some of what was lost over the centuries, we are people living in diaspora who have been detribalized and deterritorialized searching for our origins. As we search for our ancestral roots and try to understand what defines our indigeneity, we look to other Indigenous folk who have been through this process of deindianization for an example to follow in coming home to who we are. This is a cultural project that will take generations, it may be an imperfect process, but we are learning and little by little we are reconnecting with the Earth and the spirit of creation. Through “Nuestra Madre,” we are able to see the other face of the Virgen de Guadalupe which Lopez has revealed as Coatlicue de Cozcatlán, the Mother of Creation. As we decenter the West and move towards a future that centers our Indigenous ancestries, art has been an important facet of this movement, allowing artists to create work that proposes another world view that imagines a decolonial future and helps us heal from the trauma of colonization.

Lopez, Yolanda. Nuestra Madre. 1981-88. Acrylic and oil paint on masonite, 4’ x 8’.

As we consider the power of art in the process of decolonization we can refer to Gloria Anzaldúa whose work on aesthetics and conocimiento has given us a theoretical framework to understand how the creative process can heal the wounds of colonialism. Xicanx art with an Indigenista world view helps transform culture, the artist creates assemblages of conceptual references that allow for shifts of consciousness. The artist brings images and ideas together, their vision transforms reality, for some of us it reveals the world that we’ve been searching for, making connections to our ancestors to help us understand who we are. As Anzaldúa explains:

“As agents of awakening (conocimiento), las nepantleras reveal how our cultures see reality and the world. They model the transmission our culture will go through, carry visions for our cultures, preparing them for solutions to conflicts and the healing of wounds. Las nepantleras know that each of us is linked with everyone and everything in the universe and fight actively in both the material world and in the spiritual realm. Las nepantleras are spiritual activists engaged in the struggle for social, economic, and political justice, while working on spiritual transformations of selfhood.”

Anzaldua refers to the artists as nepantleras, the people who live in the liminal spaces of existence, allowing them to envision new ways to read and write the colonized reality Xicanx people face. The work they undertake allows them to consider colonial wounds that continue to haunt us and provide a space of healing, where we can come to a new understanding of the world in which we live.

Aparicio, Gina. “Ipan Nepantla Teotlaitlania Cachi Cualli Maztlacayotl” (Caught Between Worlds, Praying for A Better Future). 2019. Installation.

The ceremonial space created by the artist/nepantlera provides us with a space of healing, as Gina Aparicio created with an installation that filled an entire room “Ipan Nepantla Teotlaitlania Cachi Cualli Maztlacayotl” (Caught Between Worlds, Praying for A Better Future). The installation takes the form of a large circle about 16 feet across made of mulch, with four large sculpted figures, the Naguales, at each of the cardinal points, and in the center there is a large 8 by 8 foot carving of Coyolxauhqui, the Moon Goddess, on wood.

Aparicio, Gina. “Ipan Nepantla Teotlaitlania Cachi Cualli Maztlacayotl” (Caught Between Worlds, Praying for A Better Future). 2019. Installation.

The Naguales are the shapeshifters, spiritual beings who move through realities in search of remedies to heal their people. The Naguales are surrounded by circles of small rocks at their feet matching the color of the cardinal direction they occupy, black for the north, red for the west, yellow for the east and white for the south. Each direction has its Nagual dressed in a long white robe with large cloth necklace around their neck holding a ceremonial instrument, to the East is the Bear holding a drum, to the West is the Owl holding a flute, to the South is the Jaguar with a rattle, and to the North is the Deer holding a pipe. The stature and arrangement of the Naguales in a circle gives them the aura of ceremonial leaders, residing as guardians leading visitors through the space as they walk around the Coyolxauhqui.

As an individual enters the installation, they enter a ceremonial space created for contemplation and healing. In the circle we walk around Coyolxauhqui’s image, a recreation of the circular stone excavated in Mexico City in 1978 from the Templo Mayor. Coyolxauhqui discovered that her mother, Coatlicue, was going to give birth to Huitzilopochtli, the God of War. To stop his birth, Coyolxauhqui plotted with her 400 brothers, the stars, to kill Coatlicue. Before she could carry her plan out, Huitzilopochtli was born fully grown and attacked his sister Coyolxauhqui by dismembering and banishing her by throwing her up into the sky to become the moon along with her brothers who were thrown to the sky to become the stars. Cherrie Moraga considers this the moment when patriarchy takes over the Mexica’s culture and the world, when Huitzilopochtli dismembered the female energy and war, slavery and imperialism took over humanity. With Coyolxauhqui at the center of the installation, we are reminded of the violence she faced, the way patriarchy that continues to plague us but most importantly, the counterpoint to this phenomenon, the struggle to return to a matriarchal society.

Through her installation Aparicio initiates a ceremony to help her community heal from the traumas of patriarchy, imperialism and colonization that continue to harm our communities. Her work is an ofrenda. Before entering the installation, Aparacio invites guests to leave an offering of their own. She provides guests with small square pieces of red cloth, string, and tobacco to make prayer offerings and pin up on a brown board decorated with a peyote button surrounded by two pairs of hands and deer heads.

For the artist, this communal prayer offering “is meant to unite us as one heart, one mind, and one spirit for the healing of ourselves, our community, and our Madre Tierra.”

Aparicio, Gina. “Ipan Nepantla Teotlaitlania Cachi Cualli Maztlacayotl” (Caught Between Worlds, Praying for A Better Future). 2019. Installation.

This process allows visitors to become part of the artwork and ceremony as these tobacco offerings will be burned at the end of the exhibition and released in a ceremonial way. This moment of prayer gives the visitors a glimpse of the artist’s intention as they enter the installation and hear Aparicio’s poetry layered over a flute, taking the form of a prayer, connecting the spiritual with the political.

She prays for those crossing the border, victims of state violence, women who have experienced violence in their lives, using her words to inform people about the issues her community faces. As Anzaldua explains “En estos tiempos de la Llorona we must use creativity to jolt us into awareness of our spiritual/political problems and other major global tragedies so that we can repair el daño.” As we confront the trauma caused by imperialism and white supremacy, we seek ways to heal from the fragmentation of the self we have experienced, Aparicio connects us with Coyolxauhqui whose experience of being torn apart allows the viewer to reflect on the dismemberment we feel. Coyolxauhqui represents the pain many women face, the system that inflicts it and the struggle to create a new world. As Morraga states, “[t]hrough the mutilated women of our Indigenous American history of story – La Llorona, Coyolxauhqui, Coatlicue – I came to understand genocide, misogyny, imperialism. And I claimed them as sisters, allies in a war against forgetfulness.” Through her art, Aparicio seeks to heal and achieve integration for herself and in the process re-imagine the role of art and artists in our society as those who delve into our collective history of colonization and trauma with the aim of healing those wounds. As Coyolxauhqui is a symbol of the dismemberment for Anzaldua she is also a “symbol for reconstruction and reframing, one that allows for putting the pieces together in a new way.” The installation serves as a space to put pieces back together and for the community to connect with the ceremony and contemplate the meaning of the elements the artist has gathered in the room and to make sense of the artist’s intentions. Aparicio reaches out to her community, to Xicanx people and others living in diaspora, reflecting their history of spiritual dislocation that stems from the forced conversion of their Indigenous ancestors to Catholicism.

Aparicio’s installation is a spiritual bundle she unravels, an offering to Coyolxauhqui and her community, an opportunity to connect with an Indigenous spirituality that has been denied for hundreds of years. Similar to the bundle that Lopez opened for her community with “Nuestra Madre,” which reintroduced people to Coatlicue as the mother of creation, Aparicio seeks to reintroduce her community to another worldview that centers a matriarchal society. Through her work she initiates a ceremony and invites visitors to participate, creating tobacco ties they are able to include their prayers for a better world as part of the installation that calls for the reintegration of Coyolxauhqui and the female energy she represents.

Yolanda Lopez, Portrait of the Artist as the Virgen of Guadalupe,1978.Downloaded from www.dartmouth.edu.

Through their work these artistas Nepantleras reimagine this world “to create new ‘stories’ of identity and culture, to envision diverse futures…rethinking our narratives of history, ancestry, and even of reality itself.”

Aparicio, Gina. “Ipan Nepantla Teotlaitlania Cachi Cualli Maztlacayotl” (Caught Between Worlds, Praying for A Better Future). 2019. Installation.

Through their work they offer a new vision of the world, they manifest a spirituality that’s been obscured through colonization and create a new world where we can reconnect with the part of us that has long been denied. Lopez’ “Nuestra Madre” was an unraveling of The Virgen de Guadalupe and reconnecting us with her Indigenous origins as Coatlicue, the mother of all life. Aparicio’s work, almost thirty years later, presents a vision of spiritual healing, reconnecting us with Coyolxauhqui in a ceremony of healing from her dismemberment at the hands of patriarchy. The visitors are included in this prayer for the healing of humanity and Mother Earth from the wounds of colonialism, returning us to a matriarchy that centers those at the bottom. These artists have created a space for conversation that the next generation can enter and continue the process of opening spiritual bundles through the art they bring into the world.

Jesus Barraza

Jesus Barraza is an interdisciplinary artist with a MFA in Social Practice and a Masters in Visual Critical Studies from California College of the Arts. He holds a BA in Raza Studies from San Francisco State University. He is a co-founder of Dignidad Rebelde a graphic arts collaboration that produces screen prints, political posters and multimedia projects and a member of JustSeeds Artists Cooperative a decentralized group of political artists based in Canada, the United States and Mexico. From 2003-2010 he was a partner at Tumis design studio where he worked as web developer, graphic designer and project manager. In 2003 he was a co-founder of the screen printing studio Taller Tupac Amaru that produced political posters and fine art prints. He is currently a lecturer in the Ethnic Studies department at the University of California at Berkeley.

Works Cited

Anzaldua, Gloria. Light in the Dark/Luz En Lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality. Edited by AnaLouise Keating. Illustrated

edition. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press Books, 2015.

Aparicio, Gina. Personal Communication, October 11, 2020.

Maldonado-Torres, Nelson. “On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the Development of a Concept.” Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (May 2007): 240–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162548.

“Outline of Ten Theses on Coloniality and Decoloniality,” 37. Barcelona: Frantz Fanon Foundation, 2016. http://fondation-

frantzfanon.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/maldonado-torres_outline_of_ten_theses-10.23.16.pdf.

Moraga, Cherrie. “The (W)Rite to Remember: Indígena as Scribe 2004–5 (an Excerpt).” In A Companion to Latina/o Studies, edited by Juan

Flores and Renato Rosaldo, 376–89. Malden, MA ; Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2007.

Portilla, Miguel Leon. Tonantzin Guadalupe. Pensamiento Náhuatl y Mensaje Cristiano En El “Nican Mopohua.” México: Fondo de Cultura

Economica USA, 2000.

Rodriguez, Patrisia. Red Medicine: Traditional Indigenous Rites of Birthing and Healing. University of Arizona Press, 2012.

Revista N’OJ ©<script>document.write( new Date().getFullYear() );</script> All right reserved.