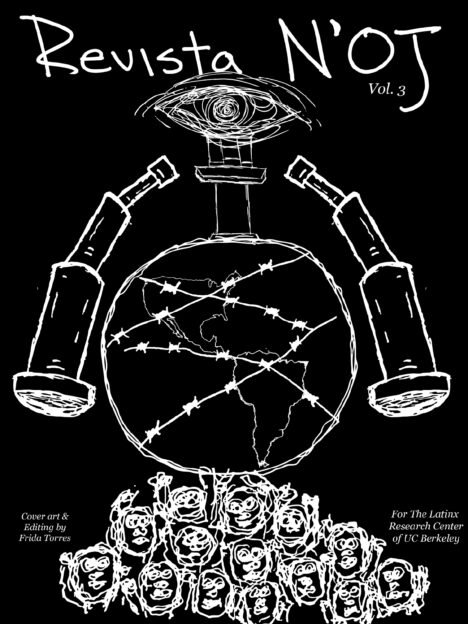

FOR THE LATINX RESEARCH CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY

Overview of the Issue

The 3rd issue of Revista N’oj focuses on the conditions of the prison industrial complex (PIC) in the U.S. during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Critical Resistance defines the PIC as “a term we use to describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems.”

All submissions are first-hand perspectives from those personally affected by the PIC: both previously and currently. Each contributor shares their personal experience through different mediums and names some of the systemic forces that make up the PIC. Some of the examples brought up by the contributors were the school to prison pipeline, hotspot policing, the militarization of police, and the mass incarceration of Black, Brown, and Indigenous persons.

Contributors

Adamu Chan, the first contributor to the issue, was incarcerated in San Quentin during COVID-19. His poem “Secret Ocean” conveys the feeling of confinement, the longing for freedom and autonomy, and is shared along with a video of an interpretive dance to the poem by Sarah Kim.

Marcus Bedford, incarcerated at the age of 19 for several decades, is a self-taught artist and created the cartoon series Calicarceration which points out the hypocrisies and ironies of the PIC. His contribution to this issue includes these comics, each of which has an explanatory blurb based on a series of interviews with Mr. Bedford.

The third contribution of this issue is a fictionalized narrative based on an interview conducted by High Desert Mutual Aid of a recently released inmate at the Adelanto Detention Center in Adelanto, California. The piece describes how COVID-19 has changed the environment of county jails and how those changes have affected the mental health of inmates.

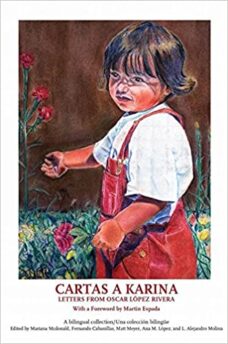

This issue of Revista N’oj also features an interview with Oscar Rivera López as the fourth contributor. In the interview, Mr. Rivera López talks about his novel Cartas a Karina, based on letters written to his granddaughter reflecting on his activism, community work, and experience of incarceration for over 30 years.

Closing Thoughts

Knowledge of prisons and the PIC, especially during the time of COVID, is sparse for most. I hope that this issue can expand our understanding and awareness of what is going on in prison facilities during a global pandemic. Also that it can serve as an example of the knowledge, creativity, humanity, and agency of persons impacted by the PIC.

Frida Pavlova Torres

Guest Editor

Revista N’oj, Issue 3, Spring 2021

Secret Ocean

Poem by Adamu Chan

Somewhere there is an ocean that I desperately need to see

To stand on its foamy shores and contemplate the vastness of existence

To yell my name into the oblivion and feel the kiss of salty mist on my face

Somewhere beyond deserts of concrete and steel,

out past morality and right and wrong

I see your footprints in the sand and anticipate our union.

“A year since the onset of the pandemic, the #StopSanQuentinOutbreak coalition ( https://stopsqoutbreak.org ) continues to call for urgent releases across California prisons, jails, and ICE detention centers, as decarceration remains the only public health solution to overcrowded prisons and the continued threat of COVID-19.

It’s been 1 year since the first COVID case inside a CA state prison & 20 CA prisons are still operating above 100% capacity. Research shows that even high-efficacy vaccines will be significantly less effective in congregate settings like prisons. We need decarceration. #ReleasesNow Toolkit : bit.ly/ReleasesNow“

CaliCarceration

Marcus Bedford

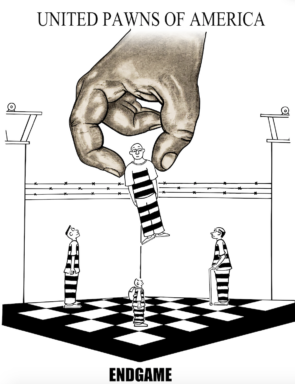

United Pawns of America

In chess, pawns are often bait for more significant pieces like knights or rooks. That is, pawns are expendable. In The United Pawns of America, Mr. Bedford reflects on how the PIC can affect persons at any age and for any amount of time even, for life. Incarceration in the U.S. can mean the loss of rights for most and a loss of agency to these prison institutions. However, in the interview, Mr. Bedford noted once reaching the other end of the board, pawn pieces can change into another. This rule is a major part of the analysis in the comic for Mr. Bedford: “You have people that are inside that just don’t know how powerful they are or how powerful they can be.”

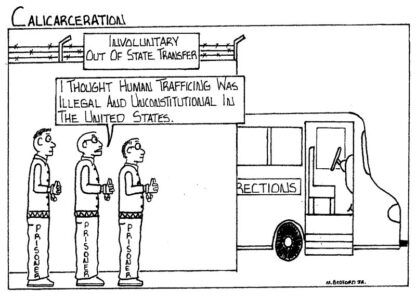

Human Trafficking

According to the United States Department of Justice: human trafficking can be defined as “[t]he recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery. (22 U.S.C. § 7102(9)).” Mr. Bedford created this comic when California prisoners were facing involuntary transfers to private prisons in Oklahoma. In it, he reflects on whether these transfers could be considered human trafficking. Mr. Bedford’s commentary becomes starker in light of a 2018 TIME piece on America’s private prison industry. TIME notes that Terrell Don Hutto, founder of CoreCivic, the company that owned these private prisons in Oklahoma, “ran a cotton plantation the size of Manhattan” in the 1960s where “mostly black convicts were forced to pick cotton from dawn to dusk for no pay.”

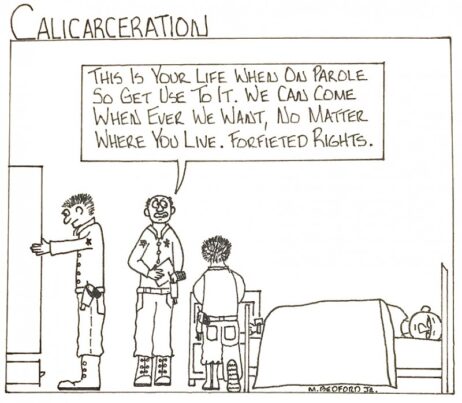

Forfeited Rights

Mr. Bedford describes his experiences while on parole. This image expands on the realities of persons on parole and the loss of rights. Even after serving time, one is still not free; and susceptible to random searches of their homes and seizure of property. To receive parole, an individual must sign conditional paperwork that can include forfeiting specific rights. Marcus Bedford states, “ That is how this system works; there is no longer a choice. Now it is either you want to go home, or you do not.”

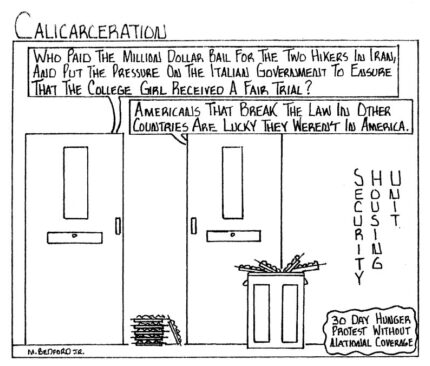

Hunger Strike

Hunger strikes are a powerful form of protest for prisoners. Between 2011 and 2013, there were historic mass hunger strikes throughout California’s state prisons. In Hunger Strike, Mr. Bedford reflects on a past protest in a facility he had been held in, where inmates were expressing solidarity with prisoners in solitary confinement. Bedford explains that this particular event began with the effort of men who were enduring solitary confinement for decades at a time. Although not widely reported, California state prisons have seen widespread hunger strikes as recently as 2021.

Image Description: Two cell doors are closed, with uneaten food trays left outside. Speech bubbles come from each door on the left, stating, “ Who paid the million-dollar bail for the two hikers in Iran and put the pressure on the Italian government to ensure that the college girl received a fair trial?” A speech bubble from the right responds, “ Americans that break the law in other countries are lucky they weren’t in America” A portion in the right reads “30-day hunger protest without national coverage.”

Calicarceration and its Founding

What is Calicarceration? It is the ‘Prison State’ known as California. “Everybody Knows Somebody” in prison, parole, probation, or on paperwork(immigrants). Don’t be fooled everyone eventually can be affected by this; one wrong move and it might be you. In Cali we are held in bondage to the ‘grind of getting it in’ no matter what. The lifestyle of a Californian is complicated to those on the outside, but it also intrigues and influences the ones that live it. From brothas in the trap house, to mothers committing money fraud just to get their children into college…that too is Calicarceration! I took my grind of bringing awareness about prison life on paper, to the streets, on T-shirts. Because of the confidence given to me by being in the Canon Human Services Center the opportunity was there to set goals and actively pursue them without stress or pressure.

JUAN SALAZAR:

Adelanto Detention & COVID-19

Edited by Daniel A. Marquez

Interview Courtesy of High Desert Mutual Aid

This fictionalized narrative is based on an interview of a man who had been recently released from Adelanto Detention Center and whose name has been changed for the sake of privacy. The interview was conducted in April of 2021 by a staff member of High Desert Mutual Aid. The responses of the interview were taken and reordered to create this interview, but aside from grammatical edits in certain instances, none of the figures or contents were edited or changed. The narrative represents an individual’s experience in a county jail in California during the times of the COVID-19 pandemic.

My name is Juan Salazar. I was incarcerated this year at Adelanto Detention Center for five months and twelve days. I went to jail for allegedly having a gun in my car. I’ve been incarcerated before, for eight months in 2009, and for four months in 2016. But now jail is different because of covid. It’s more like prison.

Covid was hard. Especially when you’re in lockdown all the time by yourself and have to wear a mask all the time. Out of the five months I was in jail, we were probably in lockdown for three. All of October, November, and part of December we were in a 23-hour lockdown.

When I first arrived, they had me and my celly, my cellmate, isolated for fourteen days. We still ended up contracting covid. It was hard, we were locked up for 23 and a half hours every day. We would just get half an hour to shower and use the phone. We had to make sure to get along because we were pretty much sleeping the whole time. There’s nothing to do. They don’t give you books. They don’t give you anything to read or anything like that.

On another occasion my neighbor had a lot of fever and was sleeping the whole time. He put in a request for medical. He got tested, but they never told him he had covid. That’s when they locked down the whole unit again. There were 30 people in our unit. A few people ended up in the infirmary. We had to wear masks every time we walked out of our cells. The officers were wearing masks too. You hardly saw faces except for your celly’s. We would even eat in our cell. Three meals a day – in our cells.

They would sell packages. Our families had to send us money to purchase the items. You were able to choose which one you wanted. They had small ones, they had big ones, some cost like $105. One is called “Wake Up.” That one was $70. The cheapest one was $23, then there was one that was $50, and the big one was $105. That was it. The $23 one just had a little bit of snacks and chocolate and stuff like that. It would last maybe four days. I wasn’t eating a lot under quarantine.

Before they had it separated. People with misdemeanors and people with high points were in separate locations. High points would be felonies like homicide or arson. Now it’s all mixed. They have you with murderers and everything. My second celly was only 18 years old. They were giving him a lot of time because he allegedly killed somebody. He was scared because he was going to do a lot of time. It was weird for me because I had never been with somebody that had allegedly killed somebody, but they’re normal.

We weren’t given any numbers. We weren’t given any direct information from anyone about the gravity of the infections. When we would ask for information, they said “We don’t know.” Every time you ask them any questions they say they don’t know or they’ll let you know. They wouldn’t even give us newspapers. Before they would give you newspapers. Mail took 40 days to arrive to us. They wouldn’t give it to you right away. They said it was because of covid.

Before we had like four hours to call our families. Now we’re only allowed a 30 minute break where we have to shower and call our families. You get no visitors during quarantine. You don’t see anybody or get to talk to anybody. It was difficult to stay in touch.

I was in a dorm the previous times I was incarcerated. This was my first time being in a cell. It was harder. Less day room. Less everything. Before they would give us outside rec, time to go outside and exercise or whatever. Now they don’t give you that anymore. Now cells pop open one at a time, and out of 16 cells in our unit, they only opened four at a time. Before it was always open. We used to kick it with homies and friends for a long time. Now we only see each other for 30 minutes but only through a window. They used to have a line where you walked and you could go talk to your friends. You cross that line, they would knock you down, you try to go to the cells, they would knock you down again. Totally different.

It’s harder. You can’t hear anything from the outside in the cells. There’s only you. There’s no window. Even to talk to another person you had to get close to the door and put your ear by it or you can’t hear anything. We tried having conversations through the wall with neighbors. We used to put our cups on the walls and we would communicate like that. Talking to your neighbors helped you stay sane, stay focused, so you don’t go crazy.

I’ve seen people go crazy in there. Some people couldn’t take it. They started crying, screaming like kids, asking for help. I saw one person go crazy. I think the social isolation had a lot to do with it because there were no windows or anything. There was a little cell that you just walked around in. You work out a lot because if not, you go crazy.

Some of my cellmates cried. I did too. I saw my first cellmate cry after like a month. We were talking about our problems and our issues. He lost his mom right before he went into jail because of covid, so he would cry a lot. I used to tell him, “cry, that will help you because you gotta let it out.” He was in prison and he had barely got out and he was only 3 months out there and he couldn’t get close to his mom because she was sick and he went into jail and he cried.

Officers are rude to you. They’re mean. They’ll find any reason to take your dayroom. They didn’t do anything when people started showing symptoms from the isolation. They didn’t care. They ignored them. There wasn’t any counseling services or psychiatric services offered. Before we would get visits but now we don’t get visits. There were two or three times I’d get anxiety and I’d start getting scared and the only way I’d feel better is sleeping. I would just ignore it and go to sleep. It’s a nasty feeling. Anxiety. You start feeling like a little kid, like being scared, and I kind of wanted to scream for help because it’s too many hours in your cell.

I used to dream a lot when I was in there. It was crazy. I used to think, “Am I going to be able to make it?” I dreamt a lot about my mom too. It was crazy. My mom telling me, “You’re going to be fine, mijo, you’re going to be fine, you’re going to be okay.” Because when I was in there, after being with somebody that killed somebody or murdered, I used to have a lot of nightmares. Like I used to dream with dead people too. It was crazy. People that were already dead, they were like “Come this way.” Some guy was telling me that he used to be my friend, but he was already dead. He was calling me in one hand and my dad was calling me in the other hand like “Ey mijo, come over here”…so it was crazy. I used to think “Am I going to be able to make it for all these 4 or 5 months? Is it going to be like this?” It’s a lot of thinking. That’s why I think you dream a lot. Because you’re all in your head.

Now that I’m with my family, I write to one of my friends who is still there. I tell him to stay strong and to keep his mind together. You’ll get out one day like me. Stay calm. Do your time. Read a lot. Work out a lot. Because if not, you start thinking about your family and that’s what makes you break down and start crying. Just stay focused on yourself.

A Talk with Oscar Rivera

Video Editing by Sarai Montes

In this interview Puerto Rican activist Oscar Rivera sits down to discuss his 2016 novel Cartas A Karina, its ties to the U.S.’s prison industrial complex, and Puerto Rico.

In 2013 Oscar López Rivera began writing to his granddaughter Karina the series that would come to be known as Cartas a Karina. The compelling content, language, and often lyric quality of the novel make this bilingual collection an indispensable reflection on Puerto Rico s status, the plight of the Puerto Rican diaspora, and the dehumanizing conditions behind US prison walls.

CONTRIBUTORS

Marcus Bedford is an artist, writer and currently runs a non-profit sober living house. While reading a prison newsletter, he came across a cartoon comic regarding prison life written by someone who had never faced incarceration. Bedford could not find accurate or unbiased portrayals of his life in any media he consumed. The misrepresentation of his life, like the current 2 million others currently incarcerated, made him create Calicarceration, a comic series depicting life in prison influenced by Bedford’s experiences.

Adamu Chan is a writer, filmmaker, and community organizer from the Bay Area. He uses his perspective and experience as a formerly incarcerated person as a lens to focus the reader’s gaze on issues related to social justice. Adamu draws inspiration from and energy from the work of James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, John Coltrane, and the art movement of his time, Hip Hop.

Oscar Lopez is a longtime Puerto Rican independence activist imprisoned for about 35 years—much of the time in solitary confinement—before President Obama commuted his sentence in January. On May 17, 2017, less than a month to go, López Rivera was released. During the 1970s and 1980s, he was a leader of the pro-independence group FALN.

High Desert Mutual Aid Society is a mutual aid group that serves the High Desert community, including Hesperia, Victorville, Adelanto, and Apple Valley. Its mission is to help others through the pandemic and build a more cooperative society. They have been providing food, supplies, and resources to the community for over a year to expand their mutual aid efforts.

Sarai Montes is an undergraduate student at UC Berkeley studying Ethnic Studies and Film & Media Studies. She is interested in using film, digital art, and other art forms as storytelling tools. She has been working on the LRC Faculty Profiles project: a series of videos centering on UCB faculty members who are Latinx and/or have research interests related to the Latinx community.

Frida Torres (Issue Editor) is a UC Berkeley Alumni from the Class of 2021 with a bachelor’s degree in Sociology and Latinx Studies. Her academic research varied from topics on Pop Culture, media’s effect on sexual education, and the policing of Latinx Women. While with the Latinx Research Center, she worked as an editor for Revista N’oj and a web designer. Frida now serves as a marketing assistant for Aunt Lute, a non-profit book publisher, and site designer for other artists, including Consuelo Jimenez Underwood.

Revista N’OJ ©<script>document.write( new Date().getFullYear() );</script> All right reserved.